One of the great ironies of science is that two of the greatest contributions in biology - the theory of evolution and the mechanistic principles of heredity - were described independently of one another within a ten year period, and yet were not integrated for 40 years. It is ironic because genetics (heredity) and evolution are so critically and intimately related...heredity describes how genetic information is passed from parent to offspring. This creates relatedness patterns within families, within species among populations, and among species. These relationships are a focus of evolutionary studies. The publications marking their official, orthodox ‘births’ were published only six years apart: Origin of Species (1859), and Experiments in Plant Hybridization (1865), yet it was nearly 80 years before these ideas were placed in their proper context within the Modern Synthetic Theory of evolution. In the first part of this course, we will examine these contributions in a historical context. We will also briefly describe the cellular context in which the genetic system operates.

5. Argument For Evolution as a Historical Fact:

Premise 1: Species that are alive today are different from those that have lived previously.

Premise 2: Spontaneous Generation is refuted, so organisms only come from other organisms.

Conclusion 1: Thus, the organisms alive today must have come from those pre-existing, yet different, species.

Conclusion 2: There must have been change through time (evolution).

Conclusion 3: The fossil record, vestigial organs, and homologies are all suggestive of descent from common ancestors.Below, the figure from The Origin of Species that shows Darwin's idea of descent from common ancestors.

So, if species do change over time (evolve), the next question is "How?" How does this change occur?

1. Transitional Observations

a.

Domesticated animals:

a.

Domesticated animals:

As a result of selective breeding, humans have taken certain species and modified them tremendously. So, from an ancestral population of wolves, we have created chihuahuas and St. Bernards. Now, there were never any Chihuahua sized wolves running around - we created this variability by progressively breeding smaller dogs with one another. Now, we have two groups, Chihuahuas and St. Bernards, that can't easily be bred together. So, we have created separate biological groups, that could be called different species. Darwin was aware of many 'breeds' of pigeons, too. These were called varieties, almost assuredly descended from a common ancestral population of rock doves (left). The KEY to the production of new varieties by humans is that humans only allowed certain organisms to breed. So, only particular traits were passed to the next generation. Darwin wondered if there was a mechanism that could do the SAME thing in nature (only allow certain organisms in a population to breed), and thereby explain the natural changes seen in the fossil record (radiational patterns of multiple species in one strata necessarily coming from fewer species in earlier strata). and implied by island faunas. Just because man does it purposefully, by design and with aforethought, doesn't mean that nature can't do it WITHOUT purpose. We put water in the freezer to PURPOSEFULLY make ice cubes... but water freezes naturally, as well - without a purpose, but with the same NATURAL CAUSE (loss of heat).

b. Reading Malthus:

b. Reading Malthus:

In 1838, Darwin read a book published in 1798 by Thomas Malthus called Essay on the Principle of Population. Malthus was a british aristocrat who was concerned that the british aristocracy might be overthrown like the French had been 10 years before (1788). He realized that all populations have the capacity to grow exponentially, but that resources are finite. As such, there will eventually be a "struggle for existence" (Darwin's words). Malthus was worried that the british population would continue to grow, and that poverty and famine would lead to revolution.

Darwin read Malthus, and wrote in his autobiography:

“In October 1838,

that is, fifteen months after I had begun my systematic enquiry, I happened

to read for amusement Malthus on Population and being well prepared to appreciate

the struggle for existence which everywhere goes on from long-continued observation

of the habits of animals and plants, it at once struck me that under these circumstances

favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be

destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species. Here, then,

I had at last got a theory by which to work; but I was so anxious to avoid prejudice,

that I determined not for some time to write even the briefest sketch of it.

In June 1842 I first allowed myself the satisfaction of writing a very brief

abstract of my theory in pencil in 35 pages; and this was enlarged during the

summer of 1844 into one of 230 pages, which I had fairly copied out and still

possess.” - The Autobiography of Charles Darwin

1809-1882 (Barlow 1958).

- If there are limited resources of food, shelter, and mates, and if organisms in a population vary, then as a consequence of this variability, some will be more likely to gain the resources than others, and will thus be more likely to mate. So, the environment will 'select' which animals in a population will mate (the ones best able to acquire the limiting resources)... and these traits that work to gain resources in this environment will be passed on at high frequency to the next generation.

2. Natural Selection: (Know this. Understand it. You WILL be asked to outline NS in this very form.)

P1: Populations over-reproduce (Malthus)

P2: resources are finite (Malthus)

C1: Eventually, a population will grow until it becomes limited by its resources. At that time, their will be a "struggle for existence" and most offspring produced will die. (Malthus)

P3: Individuals in a population vary, and some of this variation is heritable (Darwin - observations and animal/plant breeding)

C2: Variations will not have the same probability of survival and reproduction in a particular environment; those well-suited to the environment will be more likely to survive and reproduce than others, passing on the genes for these adapted traits. There will be "Differential Reproductive Success" (Observations, breeding).

C3: Over time, adaptive traits will accumulate and the characteristics in a population will change. This is lineage evolution. (Like change in horse toes in a sequence of fossil species, or like the change in the chihuahua lineage from the ancestral wolves).

Corollary:

Two sub-populations, separated in different environments, would be selected

for different traits and may subsequently lose the capacity to interbreed. At

this point, they are different biological species. This is Speciation and Radiational

Evolution. (like the production of different Finches, mockingbirds, etc. on

different islands in the galapagos, and like the radiation of St. Bernards AND

chihuahua's, which diverged from one another over time).

Darwin here provides a natural explanation for why purposeful structures and behaviors occurs in nature. Through some process unknown to him, variation arises in natural populations. These varieties differ in terms of functional efficiency in a common environment; so some improving an organisms probability of surviving and mating than others. Organisms with these beneficial traits will leave more offspring, and the frequencies of these beneficial characteristics will increase through time - much as humans select for smaller and smaller dogs. He ends The Origin of Species (1859) like this:

"It

is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of

many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting

about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these

elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on

each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around

us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being Growth with Reproduction;

Inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect

and direct action of the external conditions of life, and from use and disuse;

a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence

to Natural Selection, entailing Divergence of Character and the Extinction of

less-improved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the

most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production

of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life,

with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or

into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the

fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful

and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved". -

The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859).

"It

is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of

many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting

about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these

elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on

each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around

us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being Growth with Reproduction;

Inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect

and direct action of the external conditions of life, and from use and disuse;

a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence

to Natural Selection, entailing Divergence of Character and the Extinction of

less-improved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the

most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production

of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life,

with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or

into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the

fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful

and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved". -

The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859).

Chapter Six in "The Origin of Species" is entitled: Difficulties

on Theory

Darwin starts the chapter by writing:

"Long before having arrived at this part of my work, a crowd of difficulties will have occurred to the reader. Some of them are so grave that to this day I can never reflect on them without being staggered; but, to the best of my judgment, the greater number are only apparent, and those that are real are not, I think, fatal to my theory."

These dilemmas are:

1. How can we explain the existence of complex characteristics composed of mutually dependent parts?

- Paley's "watchmaker analogy" (1798) and the eye - the argument of design. Some elements of nature seem so complex, and composed of mutually dependent parts, that it does not seem possible that they could arise by sequential innovations. For instance, for Paley, half an eye won't work. For modern Intelligent Design proponents, the cell is called "irreducibly complex" - suggesting that it can't come from any simpler precursor - everything has to be there. (Of course, for philosophical reasons, this is about as unscientific as it gets. The idea that something is simply "too complex" to understand thwarts curiosity and stifles TRUE scientific inquiry, which is fundamentally reductionistic - as we have discussed.)

- Darwin's Solution:

"To

suppose that the eye, with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the

focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and

for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed

by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest possible

degree. Yet reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a perfect and

complex eye to one very imperfect and simple, each grade being useful to its

possessor, can be shown to exist; if further, the eye does vary ever so slightly,

and the variations be inherited, which is certainly the case; and if any variation

or modification in the organ be ever useful to an animal under changing conditions

of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could

be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, can hardly

be considered real." - The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859).

"To

suppose that the eye, with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the

focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and

for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed

by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest possible

degree. Yet reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a perfect and

complex eye to one very imperfect and simple, each grade being useful to its

possessor, can be shown to exist; if further, the eye does vary ever so slightly,

and the variations be inherited, which is certainly the case; and if any variation

or modification in the organ be ever useful to an animal under changing conditions

of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could

be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, can hardly

be considered real." - The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859).

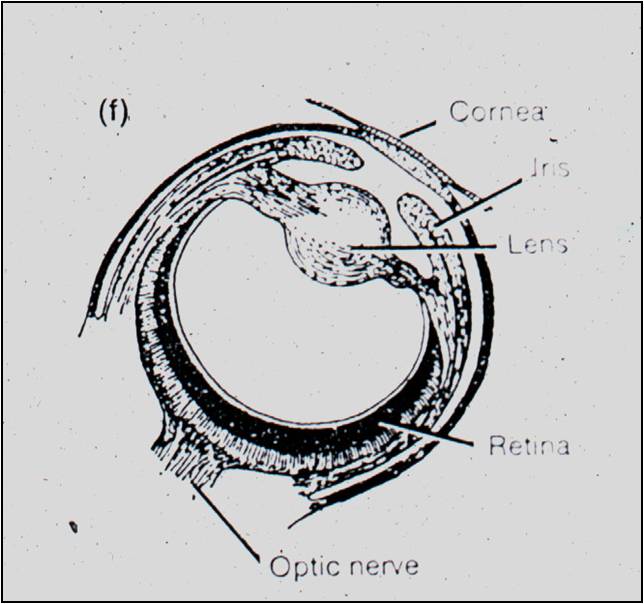

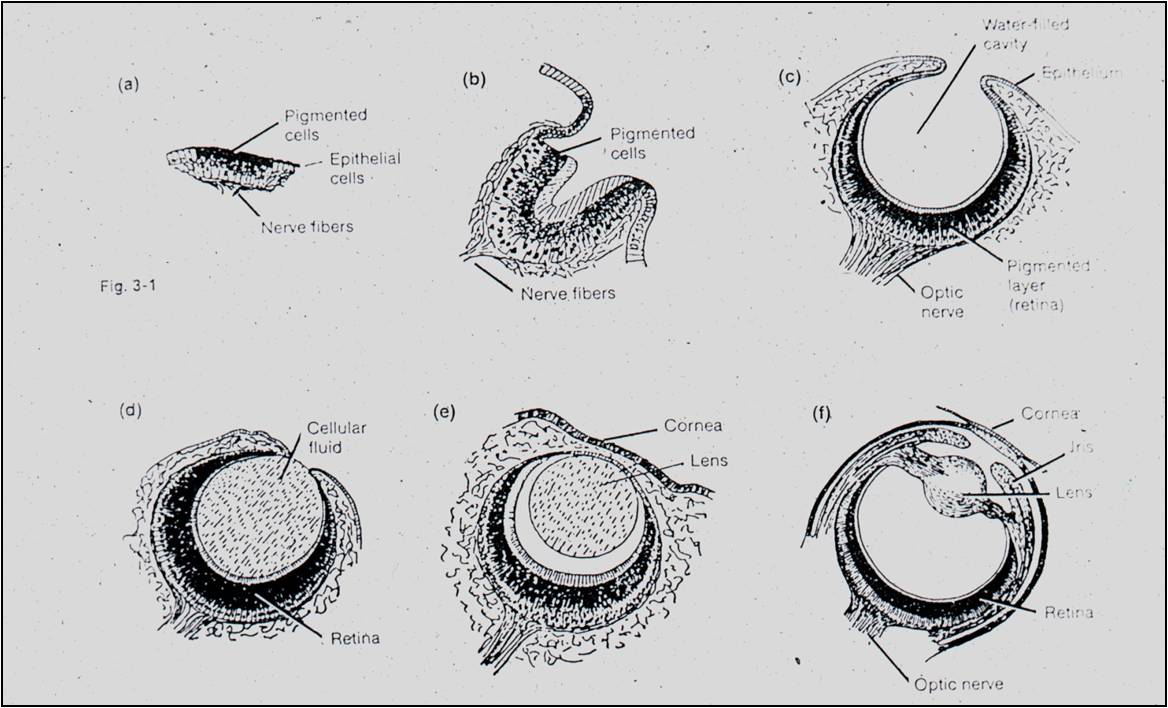

Well,

Darwin then describes the photoreceptive organs in molluscs. They range from

a sheet of receptive cells (a naked retina) to a cupped retina, to a lensless

pinhole eye, to an eye with a lens, to a camera eye. If this sequence exists

today, it is possible that this sequence could have existed through time, as

a sequential evolutionary series in eye evolution. Half an eye CAN work, if

the half you evolve first is the retina. The following videos from David

Attenborough and Richard

Dawkins are particularly good at describing the likely evolutionary scenario.

Well,

Darwin then describes the photoreceptive organs in molluscs. They range from

a sheet of receptive cells (a naked retina) to a cupped retina, to a lensless

pinhole eye, to an eye with a lens, to a camera eye. If this sequence exists

today, it is possible that this sequence could have existed through time, as

a sequential evolutionary series in eye evolution. Half an eye CAN work, if

the half you evolve first is the retina. The following videos from David

Attenborough and Richard

Dawkins are particularly good at describing the likely evolutionary scenario.

2. Where are all the intermediates?

“…why, if species have descended from other species by insensibly fine gradations, do we not everywhere see innumerable transitional forms? Why is not all nature in confusion instead of the species being, as we see them, well defined? … as by this theory innumerable transitional forms must have existed, why do we not find them embedded in countless numbers in the crust of the earth?” The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859).

Darwin was well aware that his uniformitarian hypothesis would require populations to change continuously and gradually through time. And although Lamarck's work on molluscs showed this type of change, most other lineages were best described as discontinuous and incomplete. And of course, and most importantly, the hypothesis of common ancestry predicts the existence of transitional species, representing the first evolutionary steps in the evolution of a major new group. No transitional fossils had been discovered by 1859.

There was another set of 'intermediates' that Darwin's hypothesis predicted - internediates between existing species. In other words, what would prevent the intermediates in a temporal sequence to leave descendants of their intermediate forms, thus making a continuous sequence of LIVING species between sister taxa? This continuity would make resolving one species from another almost impossible ("nature in confusion"). Darwin addressed this issue first. He said that selection, itself, would solve this issue. A more efficient descendant, with new adaptive traits, would competitively eliminate less adapted, ancestral forms:

“As natural selection acts solely by the preservation of profitable modifications, each new form will tend in a fully-stocked country to take the place of, and finally to exterminate, its own less improved parent or other less-favoured forms with which it comes into competition. Thus extinction and natural selection will, as we have seen, go hand in hand. Hence, if we look at each species as descended from some other unknown form, both the parent and all the transitional varieties will generally have been exterminated by the very process of formation and perfection of the new form.” – The Origin of Species (Darwin 1859)

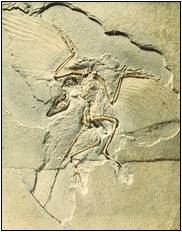

With

respect to intermediate and transitional fossils, Darwin suggested that the

fossil record was incomplete. Fossilization was a very rare event, and thus

it would be very unlikely for a representative of each species in a lineage

to have a representative preserved. However, he hope that, in time, a more complete

picture (and some truly transitional fossils) would be discovered. In 1861,

he was pleased by the discovery of Archeopteryx lithographica in Bavaria.

When previous fossils of this species had been unearthed, they were classified

as reptiles because they had teeth, fingers, and a long bony tail. But, when

this fossil (and 9 others since) were pulled from the very fine sedimentary

deposits of Bavaria, the impression of feathers were seen. So, here is an organism

with a very odd combination of traits - a lizard skeleton covered by feathers.

With

respect to intermediate and transitional fossils, Darwin suggested that the

fossil record was incomplete. Fossilization was a very rare event, and thus

it would be very unlikely for a representative of each species in a lineage

to have a representative preserved. However, he hope that, in time, a more complete

picture (and some truly transitional fossils) would be discovered. In 1861,

he was pleased by the discovery of Archeopteryx lithographica in Bavaria.

When previous fossils of this species had been unearthed, they were classified

as reptiles because they had teeth, fingers, and a long bony tail. But, when

this fossil (and 9 others since) were pulled from the very fine sedimentary

deposits of Bavaria, the impression of feathers were seen. So, here is an organism

with a very odd combination of traits - a lizard skeleton covered by feathers.

- IMPORTANT: Now, the existence of this odd animal is not the only thing that bears on evolution. Obviously, evolution does predict the existence of intermediates. But even more so, it also predicts WHEN in the fossil record this species should have lived. For instance, If Archeopteryx is a transitional species, it has to be after reptiles appear in the fossil record, and before true birds. It can't just be anywhere and be a transitional species between these groups. Well, it is just where evolutionary theory predicts it should be; after other reptiles and before all true birds. We will see lots of intermediates later in the course, when we look at post-Darwinian developments.

3. How is heritable variation produced?

Darwin's genius was seeing the importance of heritable variation; it would lead to differential reproductive success and evolutionary change. However, he did not understand how this variation was produced (mutation and recombination) or inherited (meiosis and heredity). He knew how important this was for his theory, and he was a real scientific student of hybridization experiments. One of the most difficult chapters in The Origin of Species is his extensive summary of patterns of hybridization across the animal and plant kingdoms. It is obvious that he hoped to find patterns in comparing these disparate studies that would reveal a mechanism of heredity. Unfortunately, they did not. As such, Darwin relied on those old Lamarckian ideas of "inheritance of acquired traits" (described as the effects of the 'external conditions of life') and "use and disuse":

"These laws, taken

in the largest sense, being Growth with Reproduction; Inheritance which is almost

implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect

and direct action of the external conditions of life, and from use and disuse;

a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence

to Natural Selection…". - The Origin of Species

(Darwin 1859).

Darwin proposed the existence

of particulate 'gemmules' that were present in every cell of the body. Changes

in the body changed these gemmules somehow, and before mating these gemmules

migrated to the reproductive tissue for transmission to the next generation

- explaining how acquired traits could be inherited. He even did experiment

to test his idea, which he falsified. Yet, he had no other ideas. He

died not appreciating the insights that had been made by Mendel in Austria in

1865.

E. A Summary of Darwinian Evolution:

Darwin's view of evolution can be summarized as follows:

Source of variation: UNKNOWN

but variation is observable

Causes of Evolutionary Change:

(factors that cause change in natural populations): Natural Selection

Things to know:

1. Know how Malthus's observations and conclusions were relevant to the development of Darwin's theory.

2. Know how Darwin solved Paley's dilemma regarding the stepwise evolution of a 'camera' eye.

3. Know how Darwin explained the absence of LIVING and EXTINCT intermediate forms (different processes).

Study Questions:

1. Outline the theory of natural selection as an argument, with three premises, 3 conclusions, and a corollary.

2. Outline Darwin's model of evolution, listing 'sources of variation' and 'causes of evolutionary change'.