A.

Overview:

A.

Overview:

One of the great ironies of science is that two of the greatest contributions in biology - the theory of evolution and the mechanistic principles of heredity - were described independently of one another within a ten year period, and yet were not integrated for 40 years. It is ironic because genetics (heredity) and evolution are so critically and intimately related...heredity describes how genetic information is passed from parent to offspring. This creates relatedness patterns within families, within species among populations, and among species. These relationships are a focus of evolutionary studies. The publications marking their official, orthodox �births� were published only six years apart: Origin of Species (1859), and Experiments in Plant Hybridization (1865), yet it was nearly 80 years before these ideas were placed in their proper context within the Modern Synthetic Theory of evolution. In the first part of this course, we will examine these contributions in a historical context. We will also describe the cellular context in which the genetic system operates.

A.

Overview:

A.

Overview:Darwin did three things in this book:

a. He summarized

the evidence for evolution (common descent) as an historical fact

b. He proposed mechanistic theories explaining �how� evolution

might occur (Natural Selection, use and disuse)

c. He addressed the major problems with his ideas; notably

the ideas of apparent design (Paley), the discontinuity of the fossil record

(Cuvier), and the source of observed variation.

1. Geology

a.

James

Hutton (1726-1797): Hutton was the first great british geologist.

He compared Hadrian's wall - which looks new but was 1600 years old (122 AD)

- with natural rock outcrops that were strongly weathered. Hutton concluded

that the natural outcrops must be 100's of times older. He also examined an

important formation at Siccar Point, where one series of nearly vertical strata

is overlain by another series of horizontal strata. This is now called an 'unconformity',

and Hutton explained it as follows, based on Steno's laws of superposition (the bottom vertical sediments must have been laid down first, and they must

have been laid down horizontally). Ages must have passed between each deposit,

as each turned to rock. Then, uplifts must have occurred to bend them into a

vertical aspect. Long periods of erosion must take place to wear that uplift

flat, followed by the long intervals of time needed to deposit the second horizontal

series. Also, if erosion and deposition acted slowly (as current observations

show), then it must have taken a really long time to erode mountains or build

up marine deposits (White Cliffs of Dover). He concluded that this slow, 'uniformitarian'

cycle of deposition, uplift, erosion, and deposition meant that the Earth was

unfathomably old. Indeed, the cycle may mean that it's age might not be discoverable.

In short, Hutton concludes, the Earth has "no vestige of a beginning, no prospect

of an end."

a.

James

Hutton (1726-1797): Hutton was the first great british geologist.

He compared Hadrian's wall - which looks new but was 1600 years old (122 AD)

- with natural rock outcrops that were strongly weathered. Hutton concluded

that the natural outcrops must be 100's of times older. He also examined an

important formation at Siccar Point, where one series of nearly vertical strata

is overlain by another series of horizontal strata. This is now called an 'unconformity',

and Hutton explained it as follows, based on Steno's laws of superposition (the bottom vertical sediments must have been laid down first, and they must

have been laid down horizontally). Ages must have passed between each deposit,

as each turned to rock. Then, uplifts must have occurred to bend them into a

vertical aspect. Long periods of erosion must take place to wear that uplift

flat, followed by the long intervals of time needed to deposit the second horizontal

series. Also, if erosion and deposition acted slowly (as current observations

show), then it must have taken a really long time to erode mountains or build

up marine deposits (White Cliffs of Dover). He concluded that this slow, 'uniformitarian'

cycle of deposition, uplift, erosion, and deposition meant that the Earth was

unfathomably old. Indeed, the cycle may mean that it's age might not be discoverable.

In short, Hutton concludes, the Earth has "no vestige of a beginning, no prospect

of an end."

b.

Charles Lyell (1797-1895):

Lyell promoted Hutton's ideas of a great age to the Earth and uniform rates

of change - making inferences based on the assumption of constant rates of physical

processes. Small changes, accumulating over a long time, could have big

effects. Lyell's three volume work Principles of Geology (1830-33)

opened Darwin's eyes as he read them on the H.M.S. Beagle. Geology opened "deep

time".... the Earth was at least 100's of thousands of years old, and natural

processes working slowly, gradually, and cumulatively through time could affect

large changes. Lyell was Darwin's contemporary and personal friend, although

he was distressed by Darwin's evolutionary ideas.

b.

Charles Lyell (1797-1895):

Lyell promoted Hutton's ideas of a great age to the Earth and uniform rates

of change - making inferences based on the assumption of constant rates of physical

processes. Small changes, accumulating over a long time, could have big

effects. Lyell's three volume work Principles of Geology (1830-33)

opened Darwin's eyes as he read them on the H.M.S. Beagle. Geology opened "deep

time".... the Earth was at least 100's of thousands of years old, and natural

processes working slowly, gradually, and cumulatively through time could affect

large changes. Lyell was Darwin's contemporary and personal friend, although

he was distressed by Darwin's evolutionary ideas.

2. Paleontology

Paleontology

provided a variety of interesting patterns. First, there were extinct forms

that were different from the species alive today. Although some earlier natural

philosophers suggested that the creatures might still exist in some unexplored

corner of the globe, that was a less satisfying hypothesis in the mid-1800's...

most areas of the globe had been visited by Europeans. Also, the idea of extinction

was repugnant to some people on theological grounds. If God had created a perfect

world, then extinction renders that creation imperfect. Also, if species could

go extinct since the creation, could species also come into existence since

the creation? Just how dynamic was this system?

Paleontology

provided a variety of interesting patterns. First, there were extinct forms

that were different from the species alive today. Although some earlier natural

philosophers suggested that the creatures might still exist in some unexplored

corner of the globe, that was a less satisfying hypothesis in the mid-1800's...

most areas of the globe had been visited by Europeans. Also, the idea of extinction

was repugnant to some people on theological grounds. If God had created a perfect

world, then extinction renders that creation imperfect. Also, if species could

go extinct since the creation, could species also come into existence since

the creation? Just how dynamic was this system?

Darwin was impressed by two major patterns in the fossil record.

1. The major groups of animals accumulate in an orderly manner'. Everything is not represented at the beginning. In vertebrates, for instance, the fishes appear first, and exist throughout the rest of the record. Amphibians appear next, followed by reptiles, mammals, and birds. So it is not everything at the beginning, and it is not a replacement. Where did mammals come from? Spontaneous generation had been refuted, so Darwin knew that mammals had to come from other pre-existing animals. But the only completely terrestrial vertebrates before mammals were reptiles.

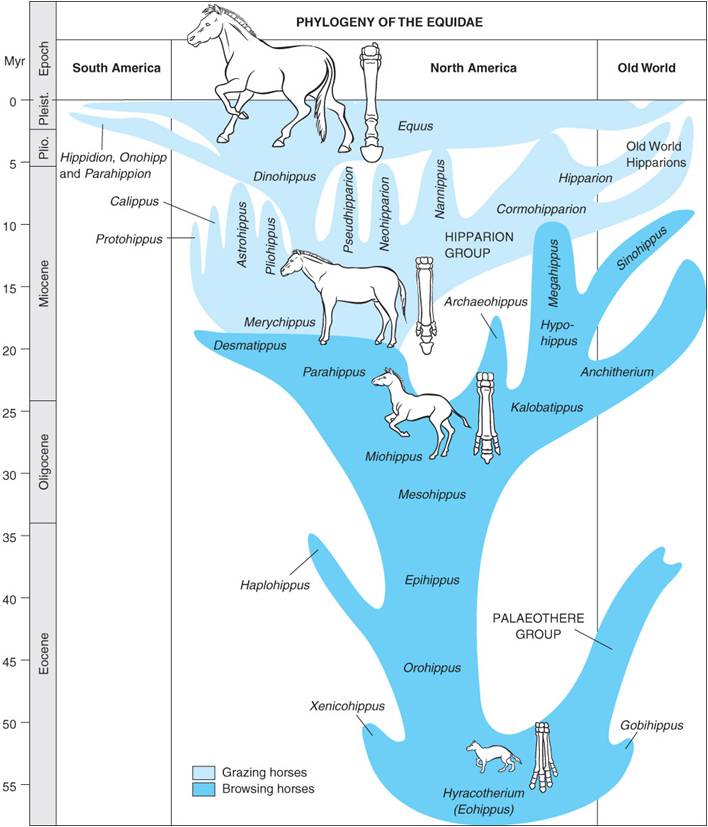

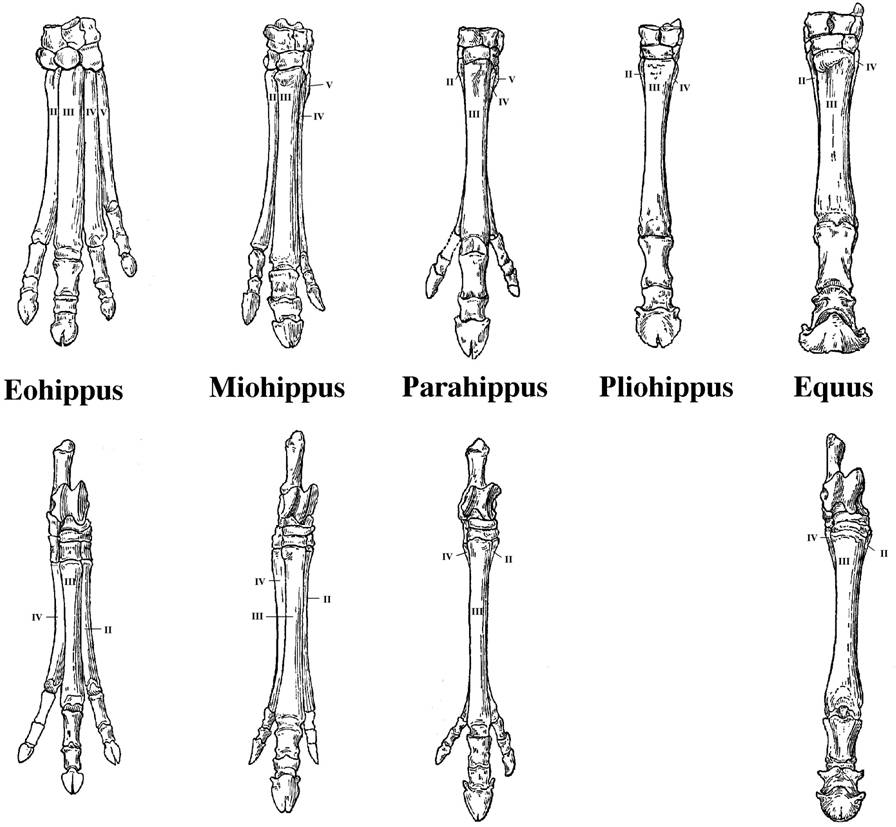

2. A second major pattern occurred within some lineages of similar organisms. Within some lineages, we seen orderly change in the size or characteristics of species in a geological sequence. For instance, consider the morphological patterns in a particular taxon (horses). Fossils in a stratigraphic sequence are similar, but often have traits that form a continuum...like the progressive loss of digits on the horse limb. And, with each innovation, there are often radiations - a "spurt" in the number of species that show this new trait. And finally, these species in recent strat are more similar to living ('extant') species than the species found in deeper, older strata. So, many of these transitional sequences terminate in living representatives.

3. Comparative Anatomy

a.

Homologous Structures

a.

Homologous Structures

Although having a different outward "look" and although used

for different purposes, they have an underlying similarity in structure - forelimbs

of vertebrates all have one long upper arm bone, two lower arm bones, a bunch

of wrist bones, and five digits. Darwin saw the similarity in structure as important.

An engineer builds different things for different purposes - cars, boats, and

airplanes are structurally DIFFERENT. Here, however, it seemed as if one basic

structure was modified for different uses. Darwin knew why siblings in a family

were similar - they had the same parents (ancestors). He reasoned that these

structural similarities in different species might be due to the same principle

- common ancestry. Also, he observed a correlation: Different uses correlated

with different environments. Could this correlation be causal?

b. Analogous

Structures

Organisms in the same environment often have a similar outward

structure or body plan. For example, flying animals all have an aerodynamic

wing that is wider at the front than at the rear. However, the wings of differnt

animals are differnt in underlying structure. Bats have fingers that support

the membraneous wing, whereas birds lack fingers and the body of the wing consists

of feathers. Insect wings don't involve the limbs at all (even though they have

6!). Again, Darwin observed this correlation with the environment: similar use

(and outward structure) in similar environments. Could this correlation be causal?

c.

Vestigial Organs

These are organs that have no function in one organism (where

they are 'vestigial') but they do function in other organisms. So, some whales

have hip bones, but no legs. Why do they have these bones? Darwin was struck

by the IMPERFECTIONS in nature, as much as the adaptations. Why do men have

nipples? Why do we have muscles that wiggle our ears? Why do we have strong

muscles in the front of our stomach, which are not "load-bearing", and weak

muscles at the base of our abdomen (which rupture in a hernia)? This is a reasonable

relationship in a quadraped, but not in a biped. Why do we have tail bones,

but no external tail? Again, these are NOT well-designed features. In fact,

attributing these imperfect designs to a perfect creator could be interpreted

as heretical. However, when we see them working in OTHER species, it suggests

that maybe we inherited them from common ancestors where they DID serve a function.

As a scientist, Darwin was trying to explain ALL the data (adaptations and imperfections),

he was not simply bringing forward only the data that supported a preferred

position (design).

d.

Embryology

d.

Embryology

Embryology reveals homologies and

vestigial structures in both the anatomy of embryos and the process of their

development. For Darwin, the notion that very different vertebrates, such as

fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, would develop from very similar

initial forms was inexplicable from a 'separate creation' perspective. For example,

why do whale embryos (like the one pictured to the right) have hind limb buds?

Why do all vertebrates have folds of tissue in the neck, when only fish develop

them into functional gill slits in the adult? Some anomalies like the recurrent

laryngeal nerves of mammals (described in your book) are explicable in a developmental,

comparative, evolutionary context. Although no modern evolutionary biologist

propounds the notion that an organism "traces their evolutionary history"

as they develop from an egg (this was Haeckel's post-Darwinian idea that "ontogeny

recapitulates phylogeny"), and Haeckel's drawings grossly exaggerated the

similarities among vertebrate embryos, embryos are far more similar to one another

than adults, and embryos are more similar to other embryos than they are to

their own adult form. As we will see when we look at modern contributions from

genetics and developmental biology, the similarities in development are even

more dramatic than anatomy alone suggests.

4. Biogeography

a. Community

convergence

Under similar environmental conditions, we find different

species filling similar ecological niches. Outward 'form' correlates with

ecological niche (role) across entire communities. So, in Australia, marsupials

fill the role of dog-like predator, cat-like predator, burrowing animal, ant-eater,

etc. These same roles are filled by outwardly similar placental mammals in South

America. However, the similarity between a wolf (placental) and a Thylacine

(marsupial - the 'tasmanian wolf') are strictly ANALOGIES. Their underlying

structure shows them to be quite different - a wolf is more similar to a ground

hog (both placentals) in underlying structure than to a thylacine.

b.

Islands Faunas

b.

Islands Faunas

Islands often have fewer species than a mainland - even a patch of mainland the same size. As such, the patterns and interactions are often simpler to describe and understand. For both Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace (the other independent author of the theory of evolution by natural selection), the study of islands was critical in to the development of their ideas.

1. Distance correlates with the uniqueness of the inhabitants: the animals on the Fauklands are the same species as on the mainland, but the Galapagos fauna is composed of unique species, found nowhere else:

"The natural history of these islands is eminently curious, and well deserves

attention. Most of the organic productions are aboriginal creations, found nowhere

else; there is even a difference between the inhabitants of the different islands;

yet all show a marked relationship with those of America, though separated from

that continent by an open space of ocean, between 500 and 600 miles in width.

The archipelago is a little world within itself, or rather a satellite attached

to America, whence it has derived a few stray colonists, and has received the

general character of its indigenous productions. Considering the small size

of the islands, we feel the more astonished at the number of their aboriginal

beings, and at their confined range. Seeing every height crowned with its crater,

and the boundaries of most of the lava- streams still distinct, we are led to

believe that within a period geologically recent the unbroken ocean was here

spread out. Hence, both in space and time, we seem to be brought somewhat near

to that great fact -- that mystery of mysteries -- the first appearance of new

beings on this earth." The Voyage of the Beagle - Darwin (1839).

2. The Galapagos fauna:

2. The Galapagos fauna:

- It was related to american fauna,

yet different: the types of animals are new world animals.... there are iguanas

like the green iguana of Central and South America, but the iguanas are different

species. So, darwin describe it as " a world within itself, or rather,

a satellite of the Americas" .... it was different, but more like the American

fauna than any other...(no chameleons, for instance, which are old world lizards...)

- It was dominated by dispersive forms. This is critical. The communities are dominated by reptiles, birds, and marine mammals. All of these organisms could MIGRATE to the islands from the mainland. (Terrestrial mammals don't migrate as well as terrestrial reptiles over open ocean. Throw a reptile in cold salty water, and: 1) its metabolism slows down (its cold), so 2) its demand for food and water decline; and 3) its scales protect it against water loss... which is why reptiles do well in the desert, too. Throw a mammal in cold salt water, and it's going to have a VERY tought time: 1) the temperature gradient between its warm body and the cold ocean is very large - in order to maintain its high body temperature against this gradient, it's metabolism has to INCREASE (to produce more heat to compensate for the heat lost to the environment). This increased metabolic demand will INCREASE the need for food and water... that's probably in pretty short supply in the open ocean; and 2) water is lost quickly from the skin to the salty ocean once the fur is wet... so, mammals are more likely to starve or die of exposure than reptiles.

- So, the islands are dominated by dispersive forms, and this suggests they came from America. But if they came from America, WHY ARE THEY DIFFERENT SPECIES THAN THOSE IN AMERICA? They must have changed since their arrival.

- There are even differences between

species on different islands. On the 14 species of finches - "Seeing this gradation

and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds,

one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago,

one species had been taken and modified for different ends." The Voyage

of the Beagle - Darwin (1839)  VIDEO

VIDEO

- Galapagos Mockingbirds Darwin thought he had one, very variable species. He

sent specimens to John Gould, the premiere ornithologist in England at the time.

On Darwin's return to England, he found out that Gould recognized the mockingbird

specimens as belonging to 4 separate species. This made Darwin consider that

maybe the variation WITHIN a species could be continuous with the variation

BETWEEN species.... maybe varieties within a species could gradually become

so different from one another that they would eventually become different species.

VIDEO

5. Argument For Evolution as a Historical Fact:

Premise 1: Species that are alive today are different from those that have lived previously.

Premise 2: Spontaneous Generation is refuted, so organisms only come from other organisms.

Conclusion 1: Thus, the organisms alive today must have come from those pre-existing, yet different, species.

Conclusion 2: There must have been change through time (evolution).

Conclusion 3: The fossil record, vestigial organs, and homologies are all suggestive of descent from common ancestors.Below, the figure from The Origin of Species that shows Darwin's idea of descent from common ancestors.

So, if species do change over time (evolve), the next question is "How?" How does this change occur?

Study Questions:

1. What is "uniformitarianism" and how was it important to the development of Darwin's ideas?

3. What observations did Hutton make, and what did he conclude from these observations?

4. What two patterns occur in the fossil record that impress Darwin regarding the hypothesis of evolution and common descent?

5. What are homologous structures? What correlations occurs with the environment?

6. What are analogous structures? What correlation occurs with the environment?

7. What are vestigial structures, and why were they so important to Darwin's refutation of Paley?

8. How did Darwin explain the existence of 'convergent communities"?

9. The Galapagos are dominated by many unique species of reptiles, birds, and marine mammals. What did this non-random assemblage suggest to Darwin about their origin, and how was evolution implied?

10. Why were the mockingbirds so critical to Darwin's ideas about the production of new species?