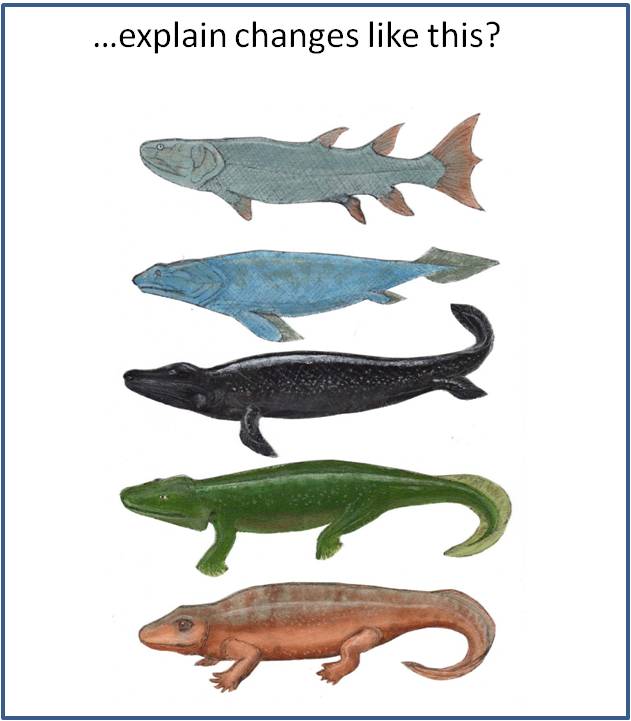

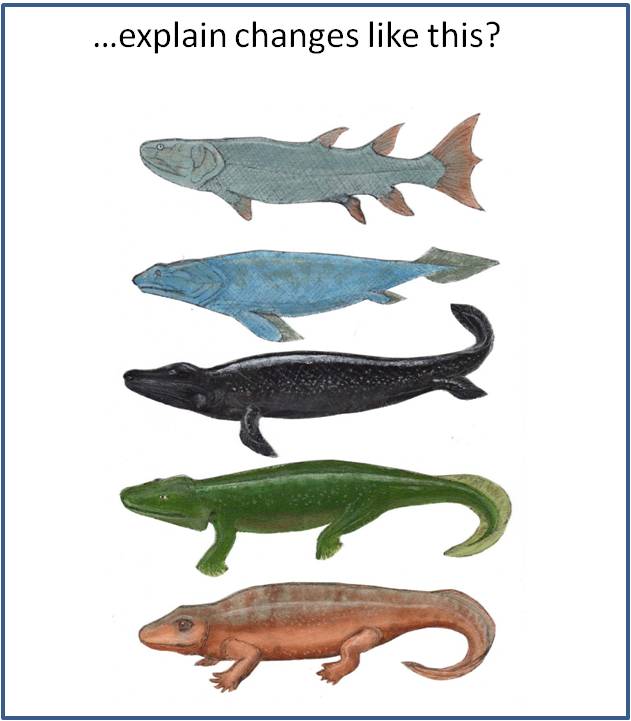

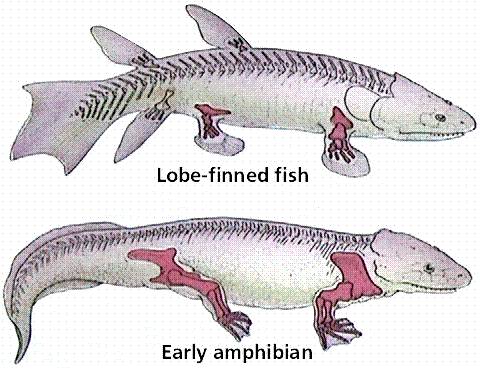

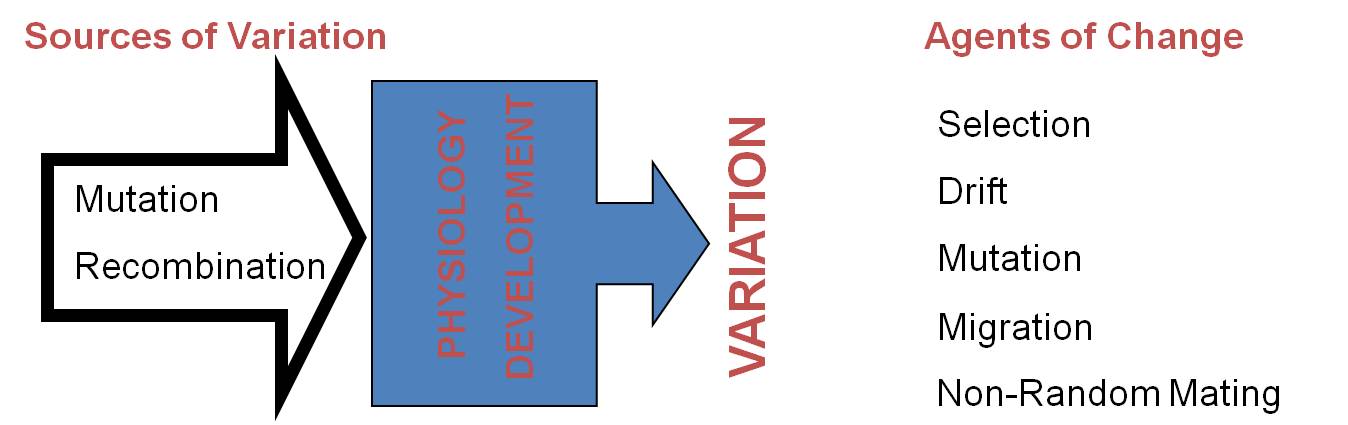

The modern synthesis and population genetics, following on classical Mendelian genetics, tended to focus on evolution as a process that occurred as a consequence of changes in the gene frequencies of structural genes - genes that code for enzymes and structural proteins. And although these protein sequences do vary over evolutionary time, and although many changes in these genes are adaptive responses to the environment, the large scale changes in evolution - like the evolution of legs in the first amphibians or wings in the first birds - seemed to be due to another cause. Why? Because fish and birds are made out of the same proteins as their ancestors (fish and archosaurs, respectively). Subtle changes in the type of collagen protein produced, or the type of hemoglobin produced, could not explain these large scale changes in morphology that are truly the most dramatic patterns in evolution. Evolving a leg from a bony fin is not a function of making a slightly different type of collagen - it is a function of putting the collagen and cells together in a new way, to create a new shape. Indeed, some biologists were so convinced that these processes were fundamentally different that they use the term 'microevolution' to explain differences within a population and 'macroevolution' to explain large scale morphological changes over geologic time.

|

|

|

| Can changes in the frequency of genes that code for different proteins within populations, even if they are adaptive like flower color, explain major differences in body plan? | The structural proteins that make up these organisms are largely the same. The differences seem to be more a function of the way the proteins and cells are put together: the way the organism develops and expresses its morphology. | It turns out that these developmental plans are coordinated by genes, too. So small changes in developmental genes can have large effects on the final shape and characteristics of the organism. |

Ever since the 1800's, embryologists were impressed by the pattern of epigenetic development - the formation of structures by embryos that did not have them in the past. So, how does a frog embryo (like the one below) that does NOT have legs today grow them tomorrow? During the 20th century, some evolutionary biologists suggested that the answer to this question might have a bearing on how legs evolved in the first place... how did fish, which do NOT have legs, evolve into amphibians that DO have legs? Starting in the 1970's, developmental biologists began to identify the genes responsible for these changes in the 'shape' of organisms - genes that influenced how balls of cells (embryos) developed into fish or amphibians, reptiles or birds. And sure enough, the insights gained in how an individual embryo grows legs gave insights into how legs may have evolved. Studying the relationship between evolution and the genes that regulate development became a field in itself: evolutionary development or "evo-devo", for short.

As with the modern synthesis, itself,

the unification of developmental biology and evolutionary biology occurred as

sc ientists, learning new things in their own fields, recognized the relevance

of their work to new areas. Consider the work of Jacob and Monod that we have

already discussed, on the lac operon. Their work showed how genes could be turned

on and off in response to environmental cues. Molecular biologists described

ways that different genes were regulated in different cells: through the action

of repressors and inducers (like transcription factors) that turn transcription

on and off (often in response to external stimuli through signal transduction),

through the differential splicing of m-RNA transcripts, through the differential

splicing of initial protein products, and through the subsequent modification

of those proteins. These are the processes that make cells in an organism different

from one another during organismal development - they make bone tissue different

from skin tissue, for example, and they determine the rate at which these tissues

will grow. They regulate the growth of tissues and organs and the subsequent

shape of an organism - its morphology. Evolutionary biologists and molecular

geneticists realized that these regulatory genes, that influence the co-ordinated

development of tissue specialization in organisms, might be the drivers of major

evolutionary innovations. The second realization was that, because most animals

share a similar embryological development, that these genes that regulate how

development occurs should be largely homologous - even if the pathways that

they regulate lead to the formation of very different (and non-homologous) structures.

ientists, learning new things in their own fields, recognized the relevance

of their work to new areas. Consider the work of Jacob and Monod that we have

already discussed, on the lac operon. Their work showed how genes could be turned

on and off in response to environmental cues. Molecular biologists described

ways that different genes were regulated in different cells: through the action

of repressors and inducers (like transcription factors) that turn transcription

on and off (often in response to external stimuli through signal transduction),

through the differential splicing of m-RNA transcripts, through the differential

splicing of initial protein products, and through the subsequent modification

of those proteins. These are the processes that make cells in an organism different

from one another during organismal development - they make bone tissue different

from skin tissue, for example, and they determine the rate at which these tissues

will grow. They regulate the growth of tissues and organs and the subsequent

shape of an organism - its morphology. Evolutionary biologists and molecular

geneticists realized that these regulatory genes, that influence the co-ordinated

development of tissue specialization in organisms, might be the drivers of major

evolutionary innovations. The second realization was that, because most animals

share a similar embryological development, that these genes that regulate how

development occurs should be largely homologous - even if the pathways that

they regulate lead to the formation of very different (and non-homologous) structures.

B.

Homeotic Genes

B.

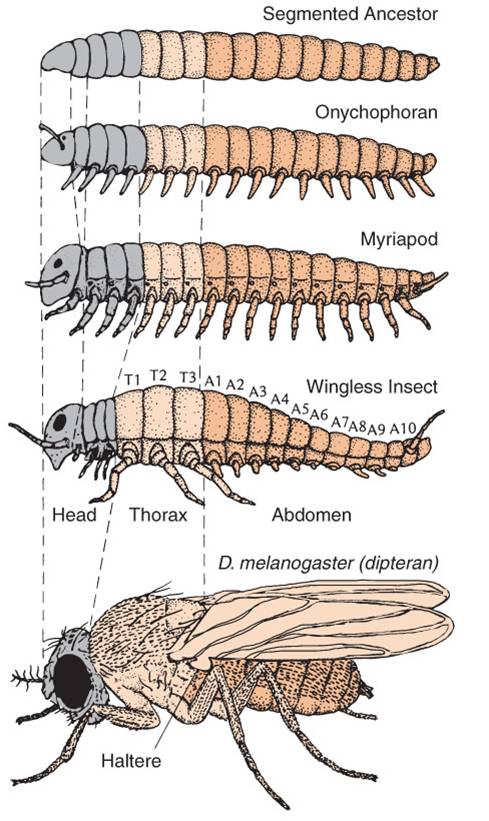

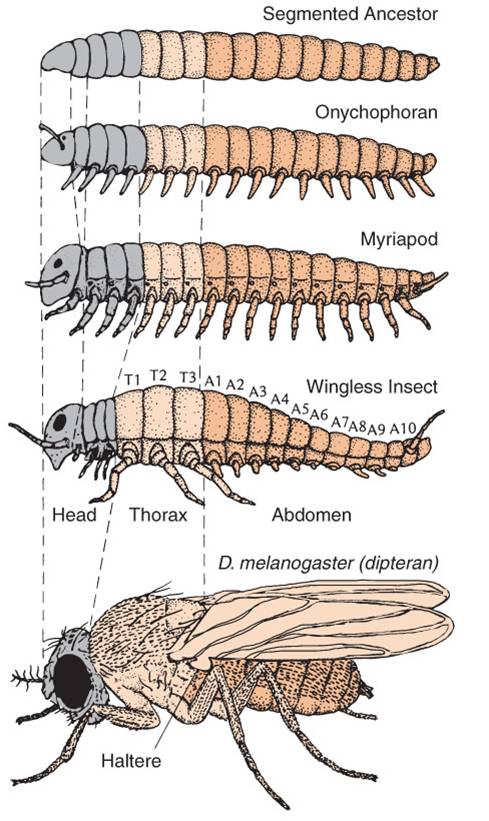

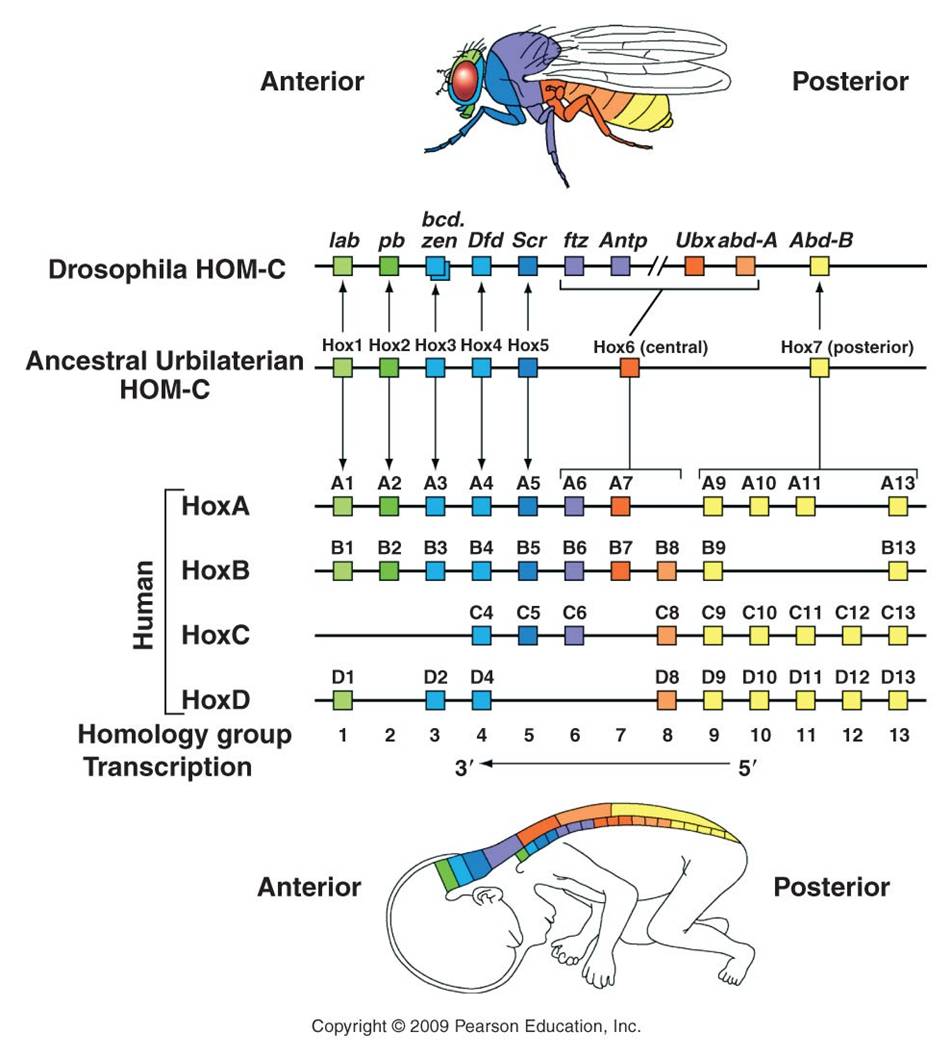

Homeotic GenesAs we will see when we get to animal diversity, almost all animals are 'segmented'. Like the segments on a worm, insect, or vertebrate spinal column, segmentation of body parts allows for specialization of structure and function. Much like gene duplication is a source of genetic novelty (keeping the original function while also allowing for the evolution of something new in the duplicated gene), dividing (or multiplying) the body into segments allows some segments to evolve new function without compromising the ability of the organism to do the 'old stuff', too. In one of the most remarkable and surprizing genetic discoveries of the last 30 years, molecular developmental geneticists were able to decipher how a group of genes act synergistically to coordinate the process of segmentation and subsequent specialization in the developing embryo. Although these genes and their activities were originally described in Drosophila fruit flies, the prediction of homology among animals for the genes regulating these fundamental processes was supported - these genes that regulate segmentation have been found in all segmented animals, from worms to vertebrates. In fact, ancestral homologs to these genes have also been found, in fewer number, in non-segmented Cnidarians (corals, jellyfish, and hydra).

The relationship between gene duplication and segment specialization is even more direct. These homeotic genes that regulate development are very similar to one another, and have undoubtedly arisen by gene duplication. One family of genes all have a very similar sequence that codes for a DNA binding domain (as we would expect for a transcription factor that must bind DNA). This sequence is called a "homeobox", and the genes in this family are called the Hox genes. So, we see the process of duplication occurring at a genetic level, and causing body segment duplication at the organism level, with the same evolutionary consequence of providing the potential for new evolutionary innovation.

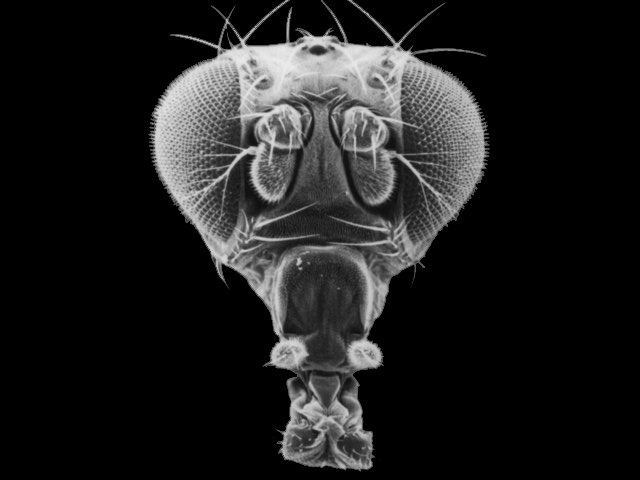

Changes in these genes can have profound effects on the final morphology of a segment. And because these genes encode transcription factors that are binding to MANY genes in the same cell, there are correlated and co-ordinated responses among the genes in a cell and the cells in that segment. Consider the "antennapedia" gene in Drosophila. It is "on" in the thoracic segments of a developing fly pupa during metamorphosis. The gene product - a transcription factor - stimulates the production of myriad genes that leads to the development of muscle, nerve, and exoskeleton tissue in the shape of a leg. This gene is normally off in head and abdominal segments, so legs don't develop there. However, mutants occur that express this gene in the head segment that usually gives rise to the antennae. In these individuals, the activation of the gene causes the development of legs on the head - where antennae should be.

|

|

|

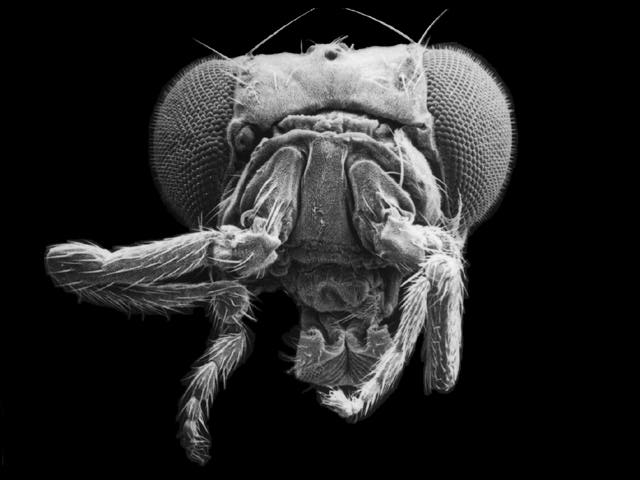

| Normal fruit fly, with normal antennae on front of head | Mutant, with legs instead of antennae | The effect of the 'Ultrabithorax' gene, on right. |

Another important hox gene in Drosophila, homologous to antennapedia and next to it (both suggesting that it is a gene duplicate) is the "ultrabithorax" (Ubx) gene. This gene codes for a m-RNA transcript that is spliced 5 different ways, and so is translated into five different transcription factor proteins. Normal expression of Ubx in the third thoracic segment of the fly interrupts development of a wing, and stimulates development of a larger set of legs on the third thoracic segment. Mutation in Ubx in this segment makes this thoracic segment develop like the second thoracic segment, growing wings and a smaller pair of legs.

Vertebrates have homologs of these same homeotic genes, with different numbers of copies of each that have arisen by duplication and deletion in the vertebrate lineage (see the colorful figure, above). Now, vertebrates don't have antennae or membraneous wings. However, these regulatory pathways still exist that turn on different sets of genes in these animals. These homeotic genes are like "genetic switches". Think about an electronic switch - it can flip on an incandescent light, a flourescent light, a blender, or a TV. The key is that the switch is linked to a given circuit, or process. One of the most dramatic examples of this 'switch' analogy involves the homeotic gene for eye development that occurs in all bilaterally symmetrical animals, including fruit flies and humans. If the gene is cut out of a developing fly embryo, then its head segments lack the gene and the fly does not produce eyes. However, if the human version of the switch is inserted in these mutants, the resulting flies develop eyes. Now, they don't develop VERTEBRATE eyes (thank goodness!), they develope the compound eyes of insects. So, the only thing the human gene did was to restore the switch, re-establishing the 'circuit' of eye development. Although the downstream effects are different (like turning on an incandescent light or florescent light), the switch is the same. A biological process can be linked to a homeotic switch by associating a gene with a binding site for that transcription factor - now that gene will be turned on when that transcription factor is present in the cell. Remember the picture of the promoter/operator region in the metallothionein IIA in humans? Remember how many different binding sites there were for different trancription factors? That gene could regulated by a variety of factors, and incorporated into a variety of metabolic/genetic processes. So, the organism's metabolism would change WITHOUT a change in the actual sequence of the metallothionein gene. Rather, there has been a change in how it is regulated.

C.

Environmental Effects and Phenotypic Plasticity

C.

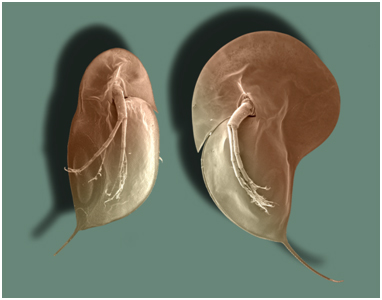

Environmental Effects and Phenotypic PlasticityThrough signal transduction, the changes occuring in one cell can affect other cells. Likewise, substances in the environment can affect gene expression - even the expression of developmental genes. For example, small freshwater crustaceans called Daphnia will grow larger spines and a larger head capsule in the presence of predatory fish. In the picture to the right, the Daphnia on the right grew in the presence of fish, and grew a bigger head capsule and larger posterior spine than the Daphnia at left, which grew in the absence of fish. So, a single genotype can produce a range of phenotypes - not just one. This is called "phenotypic plasticity", and the range of phenotypes that a genotype can produce are called its "reaction norm". As such, a phenotype is not a "hard-wired" response... rather, it represents a range of potential responses, with the observed response determined, in part, by environmental influences. This allows a population to 'experiment' with a wider range of phenotypes in a given environment - more variation upon which selection can act. Initially, a variant that is not genetically hard-wired can become encoded - as the genotype evolves to produce that phenotype more efficiently. Indeed, many genotypes may be producing the same adaptive phenotype by different genetic means - which maintains genetic variation in the population and maintains the ability to respond to still more changes in the environment. So again, evolution may not be driven through the production of new genes, but rather by the timing and coordination of gene interaction, under the influence of particular environmental cues.

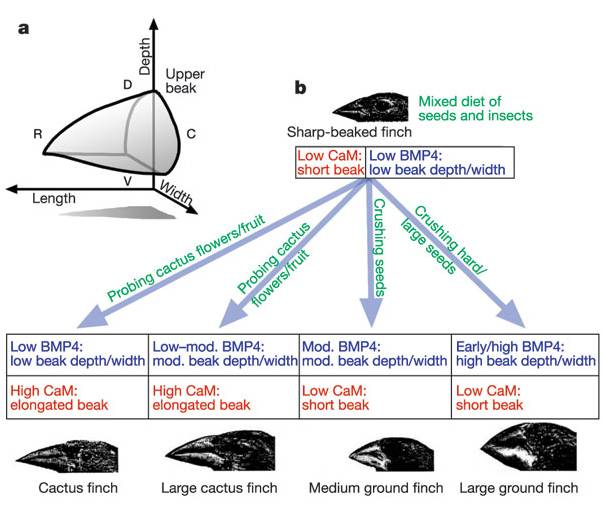

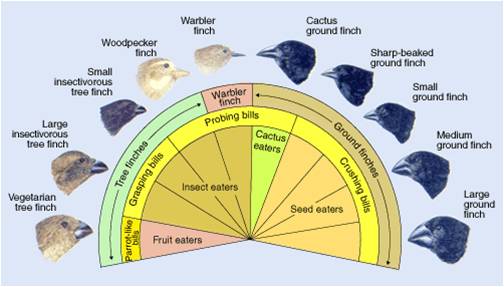

The action of regulatory genes can certainly create phenotypic variation that causes differential reproductive success (selection). Consider beak shape in Darwin's finches - one of the iconic examples of adaptive variation. How did these birds evolve different beak shapes? We can appreciate that different beaks would be adaptive in different environments with different food resources, but how are differences in beak shape encoded? It is not in the type of genes that are present, but rather in the timing and amount of their activity. In 2006, Abzhanov and coauthors described the effect of two interacting genes on beak shape. The first is BMP-4 - a "bone morphogen protein" - a transcription factor that stimulates collagen production and thus the growth of bone and cartilage. All Darwin's finches have this gene - the difference is that in large ground finches, the gene is turned on earlier in development and stays on longer than in the other species. Experiments with chicken embryos revealed that more of this protein results in larger beak development. A second gene produces calmodulin - which regulates calcium signalling in cells. High activity of this gene results in a pointy beak. Different combinations of these regulatory proteins results in different shaped beaks.

|

|

| The combined effects of two growth regulators, BMP-4 and calmodulin, influence the shape of the beak in species of Darwin's finches. | These differences in beak size and shape correlate with finch diet and ecological niche, and are believed to be important in the radiation and speciation occuring within this group. |

E.

Allometry

E.

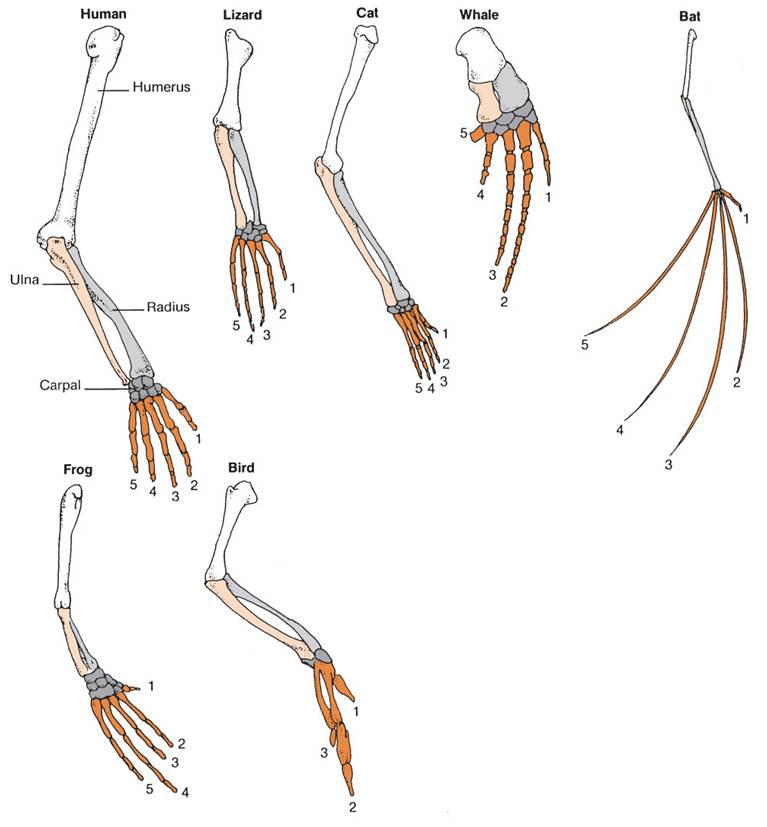

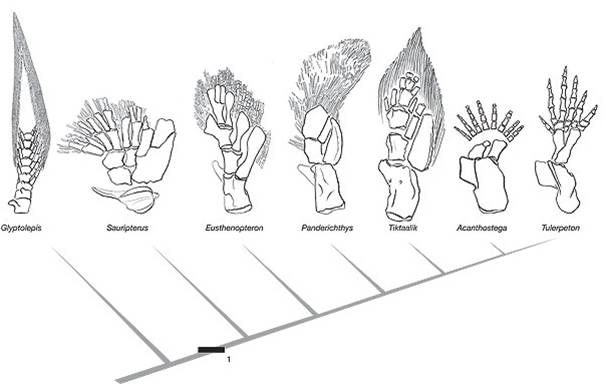

AllometryWhen we look at the diversity within a group of similar animals, what we usually see are changes in the proportion of different body parts - not really changes in the the types of parts, themselves. So, in mammals, we see the same skeletal system; the differences between mice and bats is not really in the types of bones they have, but rather in the relative sizes of the bones. So, the finger bones in a bat wing are long relative to the limb bones; whereas in mice, the finger bones are short relative to the limb bones. These differences occur because of the differences in the rates of growth of these bones during embryogenesis, and they are caused by changes in the activity of developmental genes. These changes in the relative growth of different body parts is called allometry. When we look at any large group or organisms - such as the insects or the vertebrates, what we see are differences on a single body theme - differences in shape due to relative differences in the sizes of the body parts. We now know that these differences in size, so important to creating the diversity of species that we see within a group - are largely do to differences in development. Again, the most remarkable discovery in evolutionary biology over the last 30 years is the discovery that differences between large groups of organisms - like the differences between insects and vertebrates - occurs despite an extraordinary similarity in the developmental processes and developmental genes that regulate their development.

Likewise, homologous structures in a large group of organisms, like limbs in terrestrial vertebrates, are NOT the result of changes in structural genes. These structures are built out of the same material. Rather, the differences in the relative proportions of these bones is due to differences in developmental genes that alter the relative growth rates of the bones in the limbs and digits. Of course, the changes in the frequencies of these genes can be affected by our five agents of evolutionary change. In particular, as we saw with finch beaks, these changes in the proportions of body parts can be as adaptive as the genes for structural proteins like flower color. So, although the modern synthesis described a model of microevolutionary changes in structural genes within a population, the elucidation of developmental genes that influence to large scale structure of body plans allowed evolutionary biology to explain changes in body plan with the same model - but as a change in the gene frequencies of different genes - the genes that influence the process and pattern of development, itself. So, 'macroevolutionary' differences are the result of 'microevolutionary' processes occurring in developmental genes; 'macroevolution' and 'microevolution' are not two different things.

For another example, consider one genus of Scarab beetles, the genus Onthophagus. The different beetle species in this genus have a wide variety of horn shapes and sizes; the males use the horns to battle for mates (intrasexual selection), and they may also be under some control by intersexual selection (preference of females for males with a particular horn shape). If the ratio of horn size to body size is calculated for many individuals within these species, the species cluster in a manner consistent with their hypothesized phylogenetic relationships. So, it would seem that allometric growth in horn size has been an important factor correlating with divergence in this genus.

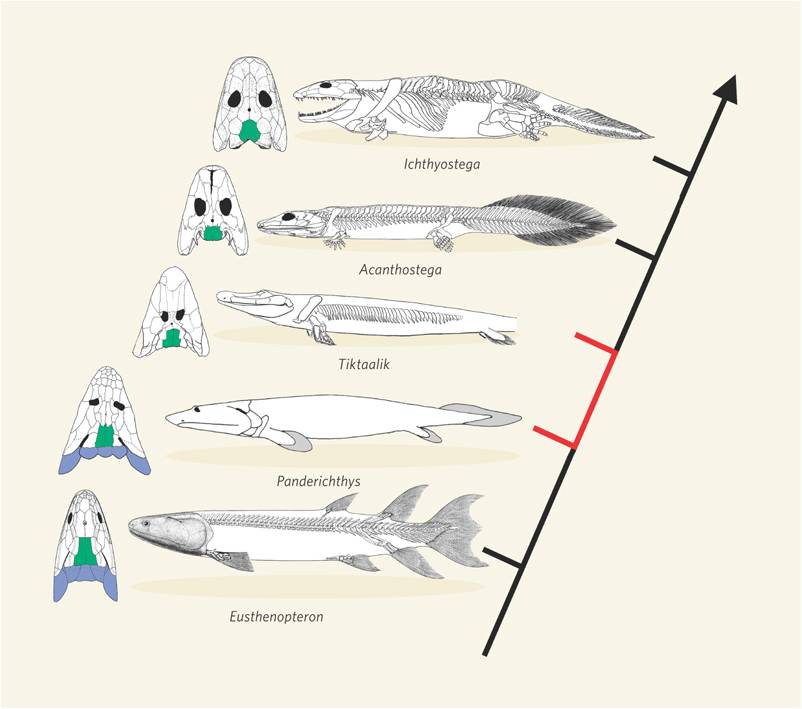

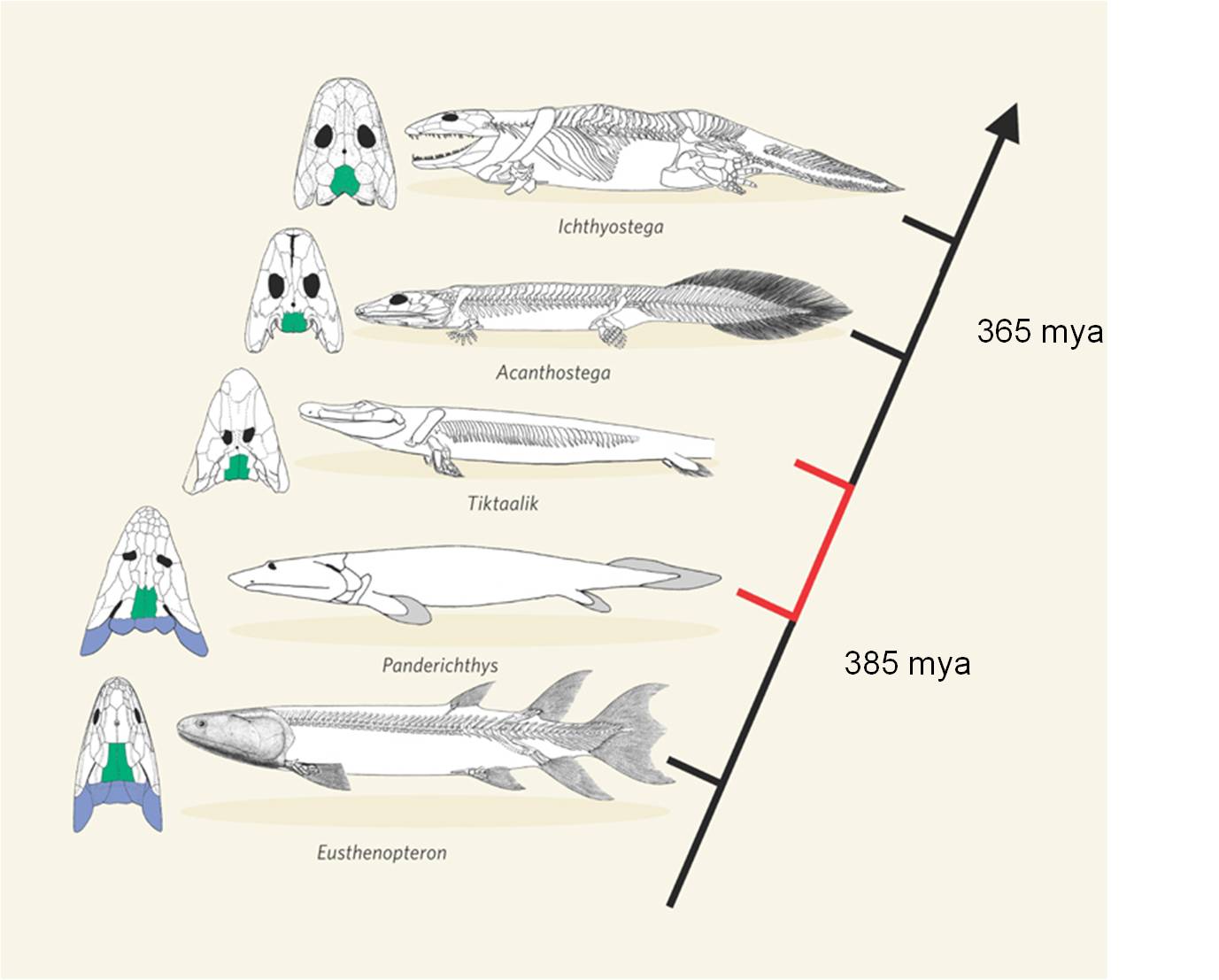

And, for yet another example, consider the evolutionary relationships between lobe-finned fishes and amphibians. There is now a very nice sequence of intermediate fossils of transitional proto-amphibians in the fossil record. When the structure of the bones in lobe-finned fishes, transitional fossils, and amphibians is examined, the changes are not in the presence of new bones, but rather in the spatial relationships, relative sizes, and developmental patterning of limb architecture. These changes were probably driven by changes in regulatory genes and transcription foactors.

|

|

|

| The limb bones in lobe finned fishes and terrestrial vertebrates are homologous. | The transition from fish to terrestrial amphibians is well documented in the fossil record | The change in forelimb structure is really one of a change in the relative position of skeletal units and skeletal architecture. |

Large

scale differences in morphology that define the major groups of organisms -

which are sometimes refered to as "macroevolutionary" patterns - are

probably not caused by changes in structural genes. However, this does not mean

that these changes are orchestrated by different processes. Rather, these macroevolutionary

changes that occur in large-scale morphological characteristics are probably

caused by changes in the action of regulatory genes like transcription factors,

which affect developmental processes. The changes in the action of these genes

can be modeled by population genetics, too; and we would expect the effects

of the genes to be acted on by natural selection, genetic drift, positive assortative

mating, mutation, and migration. So, in this sense, microevolutionary changes

that occur within a population at a given locus can cause the macroevolutionary

patterns that we see in the evolution of new, different types of organisms.

It just that those microevolutionary changes in gene frequencies are occurring

at the loci of regulatory genes that co-ordinate morphological development in

that population.

Large

scale differences in morphology that define the major groups of organisms -

which are sometimes refered to as "macroevolutionary" patterns - are

probably not caused by changes in structural genes. However, this does not mean

that these changes are orchestrated by different processes. Rather, these macroevolutionary

changes that occur in large-scale morphological characteristics are probably

caused by changes in the action of regulatory genes like transcription factors,

which affect developmental processes. The changes in the action of these genes

can be modeled by population genetics, too; and we would expect the effects

of the genes to be acted on by natural selection, genetic drift, positive assortative

mating, mutation, and migration. So, in this sense, microevolutionary changes

that occur within a population at a given locus can cause the macroevolutionary

patterns that we see in the evolution of new, different types of organisms.

It just that those microevolutionary changes in gene frequencies are occurring

at the loci of regulatory genes that co-ordinate morphological development in

that population.

One of Darwin's principle contributions is the theory of common ancestry - the theory that species are biologically related to one another and are descended from shared ("common" meant as "in common") ancestral species. Darwin's other major contribution - natural selection - describes how this process of divergence might take place: as a consequence of populations adapting to different environments and becoming different from one another. Of course, as Darwin realized, these changes must be heritable - or genetic. We now know that there are a variety of other agents of evolutionary change that can cause change in the genetic structure of a population. All of these changes can, in principle, create enough genetic divergence between populations to render mating, fusion of gametes, or correct development of offspring unlikely. When this occurs, the two populations have achieved "reproductive isolation" - the inability to mate and produce offspring with members of another group. In a genetic sense, this is what we mean by the term 'species'. Although there are situations where this definition is problematic (see below), there is a biological realism to this definition for sexually reproducing organisms. Populations that become reproductive isolated from other groups have a unique biological and genetic identity. Their gene pool is now independent of other genes pools, and changes that occur in this gene pool will be unique (even just by chance genetic drift) and will make this population even more different from other groups. In other words, once a population is reproductively isolated from other groups, it will tend to become even more genetically different and biologically unique.

1.

Morphological Species Concept:

1.

Morphological Species Concept:

"A species is what a competant taxonomist says is a species", based a sets of characteristics that correlate within a group and not between groups. Often, this is done using lots of characters and a large statistical analysis. In many cases, the analysis and categorization of fossil species or museum specimens still rests on this approach. Although morphology is often a good correlate for biological uniqueness, there are a couple problems that can arise. "Sibling species" are morphological indistinguishable, but genetic analyses reveal that they do not breed with one another. Likewise, polymorphic species are species that harbor morphologically different subpopulations that breed together. Members of these subgroups are often so different that they were classified as separate species until their mating habits and genetic similarity were revealed. For example, in the picture to the right, all the butterflies in the left column are members of the same species, and all the butterflies in the right column are members of a single different species. They do hybridize in one part of their range, creating the morph seen between the columns.

2. Biological Species Concept:

Ernst Mayr, one of the principal authors of the modern synthetic theory and one of the most prominent evolutionary biologists of the 20th century, created the 'biological species concept' in the 1940's. As described above, Mayr defined a species as "a group of organisms that mate among themselves and are reproductively isolated from other such groups." Although this is a biologically attractive definition (because we are trying to identify biological units that differ, and if they don't breed then they do or will differ, genetically), there are some real problems that can occur.

- for many species (fossils and living) the reproductive biology is not described. How shall we classify these organisms?

- for asexual species, reproductive isolation occurs at the clone level...is each clone a species?

-

finally, we cannot simply use genetic differences as a determinant. Although

reproductive isolation and biological uniqueness correlates with genetic difference,

sometimes single genes can cause populations to become reproductively isolated.

In other cases, genes are transferred laterally - between unrelated organisms

by viruses - and so genetic similarity at a given locus may not indicate recent

ancestry. Indeed, horizontal gene transfer may be so common in prokaryotes that

a pattern of divergence (family 'tree') may be impossible to recreate and may

not be the correct representation of evolutionary relationships, anyway. In

other words, if a lineage receives 30% of its genes from organisms that it is

not decended from, then is "descent with modification" and common

ancestry the most correct and useful and predictive model to describe the evolution

of this group?

-

finally, we cannot simply use genetic differences as a determinant. Although

reproductive isolation and biological uniqueness correlates with genetic difference,

sometimes single genes can cause populations to become reproductively isolated.

In other cases, genes are transferred laterally - between unrelated organisms

by viruses - and so genetic similarity at a given locus may not indicate recent

ancestry. Indeed, horizontal gene transfer may be so common in prokaryotes that

a pattern of divergence (family 'tree') may be impossible to recreate and may

not be the correct representation of evolutionary relationships, anyway. In

other words, if a lineage receives 30% of its genes from organisms that it is

not decended from, then is "descent with modification" and common

ancestry the most correct and useful and predictive model to describe the evolution

of this group?

4. The issue:

The problem of classifying species is caused, in part, with the very process of speciation. Even in a classic case of two isolated populations diverging genetically, this process of genetic divergence may be continuousover timeor space; making the assignment of categorical distinctions problematic. When (or whre across the range) in this continuous process should they be called different species? To name a species is to create a discrete group; however, all biological groups may not be discrete - they may still exhibit some continuous variation with another group - even to the point that they still reproduce at some level (hybridization). This is simply a consequence of how speciation occurs and which genetic differences have occurred.

Well, that obviously depends on how you are classifying them! However, we will proceed with the rest of this lecture applying the biological species concept of Mayr. So, the question changes from 'how does speciation occur?' to 'how does reproductive isolation occur?' Over the years, several 'reproductive isolating mechanisms' have been identified. Typically, these are divided into factors that act before (pre-zygotic) or after (post-zygotic) the formation of a zygote.

1. Pre-zygotic Isolating Mechanisms: What could prevent two populations from mating and forming a zygote?

- Geographic isolation: they are in different places and so do not reproduce. Tigers and lions now have ranges that do not overlap, and so they do not mate in nature - even though they will mate in captivity. For 99.999% of biologists, lions and tigers are still 'good' species.

- Temporal isolation: they are in the same place, but they are active or breed at different times of day or year. Many closely related insects have adapted to different temperature environments, or different host plants that are available at different times, and so they breed a few weeks apart and are reproductively isolated.

- Behavioral isolation: they live in the same place and breed at the same time, but do not recognize one another as suitable mates. Many waterfowl may mate at the same time in the same mating grounds, but they have very elaborate and species-specific courtship rituals that reduce the likelihood of interspecific mating.

- Mechanical isolation: they attempt to mate with each other but their genitalia do not fit. For arthropods with 'lock-and-key' copulatory organs, small changes in the shapes of the organs may result in reproductive isolation.

-

Chemical isolation: the sperm may not tolerate the chemical environment of the

female reproductve tract. Chemical isolation is also common in plants, where

the pollen must digest a pollen tube through the style to reach the ovule and

egg. Chemical incompatibility can result when the pollen does not have the correct

digestive enzymes.

-

Chemical isolation: the sperm may not tolerate the chemical environment of the

female reproductve tract. Chemical isolation is also common in plants, where

the pollen must digest a pollen tube through the style to reach the ovule and

egg. Chemical incompatibility can result when the pollen does not have the correct

digestive enzymes.

2. Post-Zygotic Isolating Mechanisms: What cound prevent the zygote from establishing a new population or transferring genes between populations?

- Genomic incompatibility: The zygote forms but the genomes are too different to orchestrate a coordinated development. No embryonic development or incorrect development occurs and no offspring is produced.

- Hybrid sterility: an offspring is produced, but because the chromosomes are not homologous, sexual reproduction is impossible and the hybrid is sterile. So, the two populations can get genes to combine, but they cannot get genes from one population into the other - just into the hybrid. So, the populations are still gnetically isolated from one another. (Donkeys and horses mate to make sterile mules).

- Low hybrid fitness: The hybrid can reproduce, but does so at a lower level than members of the original populations. In this case, the hybrid may be able to transfer genes between populations, but the frequency of hybrids will remain low as they are selected against. Many plants show this pattern. There are many oaks such as Northern red oak, scarlet oak, and southern red oak that hybridize.

1. Radioactive Decay and Geological Clocks

Darwin had guessed that the earth had to be at least 300 million years old to explain the evolution of life through the stately process of natural selection. W. Thompson ("Lord Kelvin") was a physicist who demonstrated that the Earth could be no more than 24 million years old. He did this by calculating how long it would take for a molten object with the Earth's mass to cool to the current temperature of the Earth. However, he made his predictions before Becquerel and the Curies discovered radioactivity - a process that releases heat and keeps the Earth warmer than it "should be" (based on Thompson's inference). After the Curies discovered radium and studied radiactivity (1898), Ernst Rutherford realized that the regular rate of decay could be used to age rocks.

a.

Principle:

- measure amt of parent and daughter isotopes = total initial parental

- with the measureable1/2 life, determine time needed to decay this fraction

- K40-Ar40 suppose 1/2 of total is Ar40 = 1.3by

(Now, you might say "be real"! How can we measure something that is this slow?)

Well, 40 grams of Potassium (K)

contains:

6.0 x 1023 atoms (Avogadro's number, remember that little chemistry

tid-bit?). So, For 1/2 of them to change, that would be:

3.0 x 1023 atoms in 1.3 billion years (1.3 x 109)

So, divide 3.0 x 1023 by 1.3 x 109 = 2.3 X 1014 atoms/year.

Then, divide 2.3 x 1014 by 365 (3.65 x 102) days per year

= 0.62 x 1012 atoms per day ( shift decimal = 6.2 x 1011)

Then, divide 6.2 x 1011 by 24*60*60 = 86,400 seconds/day: (= 8.64

x 104) = 0.7 x 107 atoms per second

0.7 x 107 = 7 x 106 = 7 million atoms changing from Potassium

to Argon every second!!!

This 'decay' gives off energy - radiation that is detectible and measureable by Geiger counters and similar instruments. It is actually an easily measured rate. And you can come back and measure it again tomorrow, next week, next year, or in 50 years; and it has always been the same.

b. Different Clocks

The K-Ar clock is ok for measuring things that happened billions of years ago, but it is not a good clock for things happening hundreds or thousands of years ago because the rate of change is so slow. It would be like measuring an olympic 100m sprint (which last less than 10 seconds these days) with a 2-minute hour-glass egg timer. After ten seconds, only a few grains of sand will have fallen. For measuring anything, you need a gauge with the correct level of resolution. For an olympic 100m sprint, an electronic 'stopwatch' measuring to the thousandths of a second is needed. For measuring the marathon, you don't want that type of resolution; an analog clock that measures hours, minutes, and seconds is probably appropriate. Of course, when you measure the same event with different types of clocks, they should all give roughly the same answer, even if the answers differ in precision. Luckily, there are different isotopic series that give resolution at different time scales:

C14 - decays to C12 with a half-life

of 5730 years

Longer periods - use different elements with longer half-lives

- K40 decays to Ar40 at a rate of 50%/1.3 b years

- U238 - Pb208 = 4.5 by

- Rb87 - St87 = 47 by

- U238 - Thorium 230 = 80,000

- U235 - Protactinium231 = 34,000

c. Tests of Corroboration

We gain greater confidence in a conclusion if it is supported by multiple, independent pieces of evidence. One eyewitness to a crime is ok, but three different people who all tell the same story are far more convincing. Because the decay process in one element present in rock has no effect on the way other elements decay, the decay series are independent of one another. So, one rock could be aged using the K-Ar clock, the Rb-St clock, and the U-Pb clock. If we get roughly the same age using these three different clocks, we would be more confident in that age. There are other corroborating methods, too, that don't involve decay, at all. For example, we can carbon-date material from Pompeii, which we know from historical record should date to 79ACE. Indeed, they do, corroborating the use of radiocarbon dating. One of the most dramatic corroborations involves predictions from astronomers. Astronomers have postulated that, because of tidal friction between the water in the ocean and the earth, the rotation of the Earth has been slowing down over time. In fact, astronomers have calculated that, based on the masses of the oceans and the Earth, and the frictional coefficient of water against land, that the length of an Earth's rotation (a day) has slowed at a rate of 2 seconds every 100,000 years. (So days were SHORTER in the past and have SLOWED to the current 24 period). This process would not affect the time it takes the Earth to orbit the sun, however. So, it would take a year for the Earth to orbit the sun, but the Earth would be spinning on its axis more rapidly in the past. This means that a year in the past would have MORE days than it does now. Indeed, astrophysicists predict that, based on tidal friction, a year 380 million years ago would have contained 400 days. Wow... crazy. Well, corals lay down a layer of calcium carbonate 'shell' every day. There are seasonal changes in the thickness of the layers, so years can be distinguished, too. Some corals have been dated by radioactive decay to be 380 million years old. If this age based on decay is correct, and if the astrophysicists are correct, then they should have 400 daily layers of growth within each yearly band. They do. So, we can use basic physics to predict the "age" of a coral. And when we compare that "age" to the "age" determined by radioactive decay, the ages are the same. So, either they are both true, or they are both wrong in the same way. It is unlikely that we have such basic physics wrong. Very unlikely. So, the Earth is, indeed, very very old. Radioactive decay is constant; if it wasn't, or if it hadn't been in the past, none of these comparisons would work. period. But they DO work, and so it is irrational to conclude that the Earth is young, or that radioactive dating doesn't work or is somehow "dubious". Again, our ability to harness the power of radioactive decay in nuclear reactors is powerful testimony to the degree of confidence we have in our knowledge and understanding of the decay process. And thus, we have great confidence in the great age of the Earth.

2. 'Transitional' fossils

One of Darwin's dilemmas was the lack of continuous sequences of fossils that preserve a complete record of evolutionary change. In 1859, the fossil record was best described as 'discontinuous' for most lineages. Of particular interest to Darwin's model of common descent was the absence of 'transitional' fossils - fossils that showed the nascent beginnings of a major new type of organism evolving from more primitive stock. In the last 150 years, paleontology has unearthed millions of fossils and many have been placed in very complete sequences. They provide a solution to Darwin's dilemma and also allow us to reconstruct phylogenies. We will take a look at some of the more remarkable transitional sequences that have been documented in the evolution of vertebrates.

Transitional fossils are important in two ways. First, they contain a complement of traits that makes them hard to pigeonhole into one group of organisms or another. In other words, they have a combination of traits from two separate groups (an intermediate morphology).

But this is not all. I mean, there are alot of crazy organisms out there. The existence of a weird combination of traits does not mean the organism is necessarily a transitional form, nor does this support common ancestry in and of itself. Evolution does something more than simply predict the existence of transitional forms - if predicts WHEN these forms should exist. Let's apply these ideas to some real fossils.

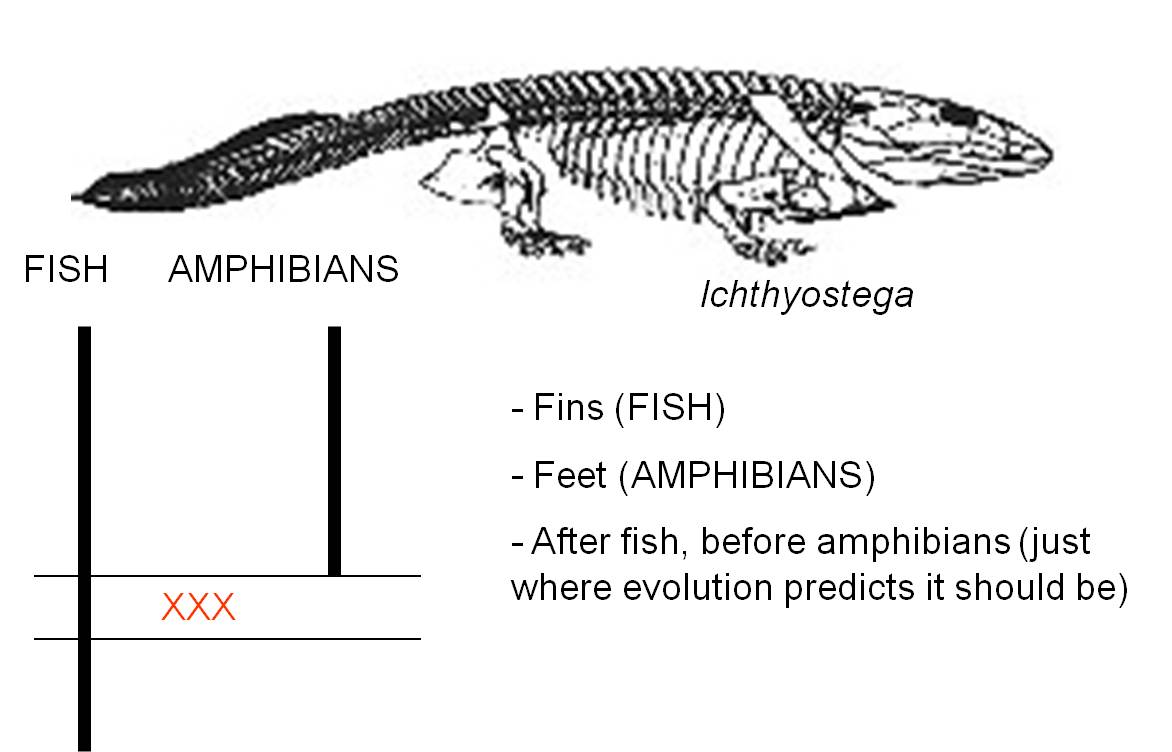

a. Ichthyostega spp. and the evolution of tetrapods

Darwin hypothesized that amphibians evolved from fish. This created a few important problems - how did lungs and feet evolve? In 1929, several species with a mix of fish and amphibain characters were discovered in Greenland and placed within the genus Ichthyostega. These animals had lungs and gills - an obviously intermediate morphology. And they had tails with cartilagineous rays in the fin, like a fish tail. But these animals also had feet. The legs were probably not strong enough to bear the entire weight of the animal, but it was a true tetrapod. So, it had a suite of fish and amphibian traits. However, that is not enough. To be a transitional fossil and to truly test the hypothesis that this animal is an ancestor of amphibians and a descendant of fish, it must come after true fish and before true amphibians. Indeed, that is right where it is.

This transition between fish and land animals was one of the most important evolutionary transitions in the history of life. Since 1929, many fossils have been found that form a very complete transitional sequence, linking lobe-finned fish like Panderichthyes to proto-amphibians like Ichthyostega and Acanthostega. In 2004, an exceptional fossil was found in Northern Canada that was intermediate between Panderichthyes and Ichthyostega. Tiktaalik rosae was such a beautiful transitional form that it was dubbed the "fish-o-pod". The animal has short bony forelimbs that terminate in fins, not feet. However, the limbs are able to support weight, and have a wrist-like joint that allows the limb to pivot and propel the animal forward. It has a decidedly fish-like body, but an Ichthyostegan head and intermediate limbs.

|

|

| Ichthyostega was one of the first fossils that bridged the gap between fish and amphibians | Now, a series of intermediates shows the transition from ancestral, lobe-finned fishes, through limbed fishes like the "fish-a-pod" Tiktaalik, to amphibians |

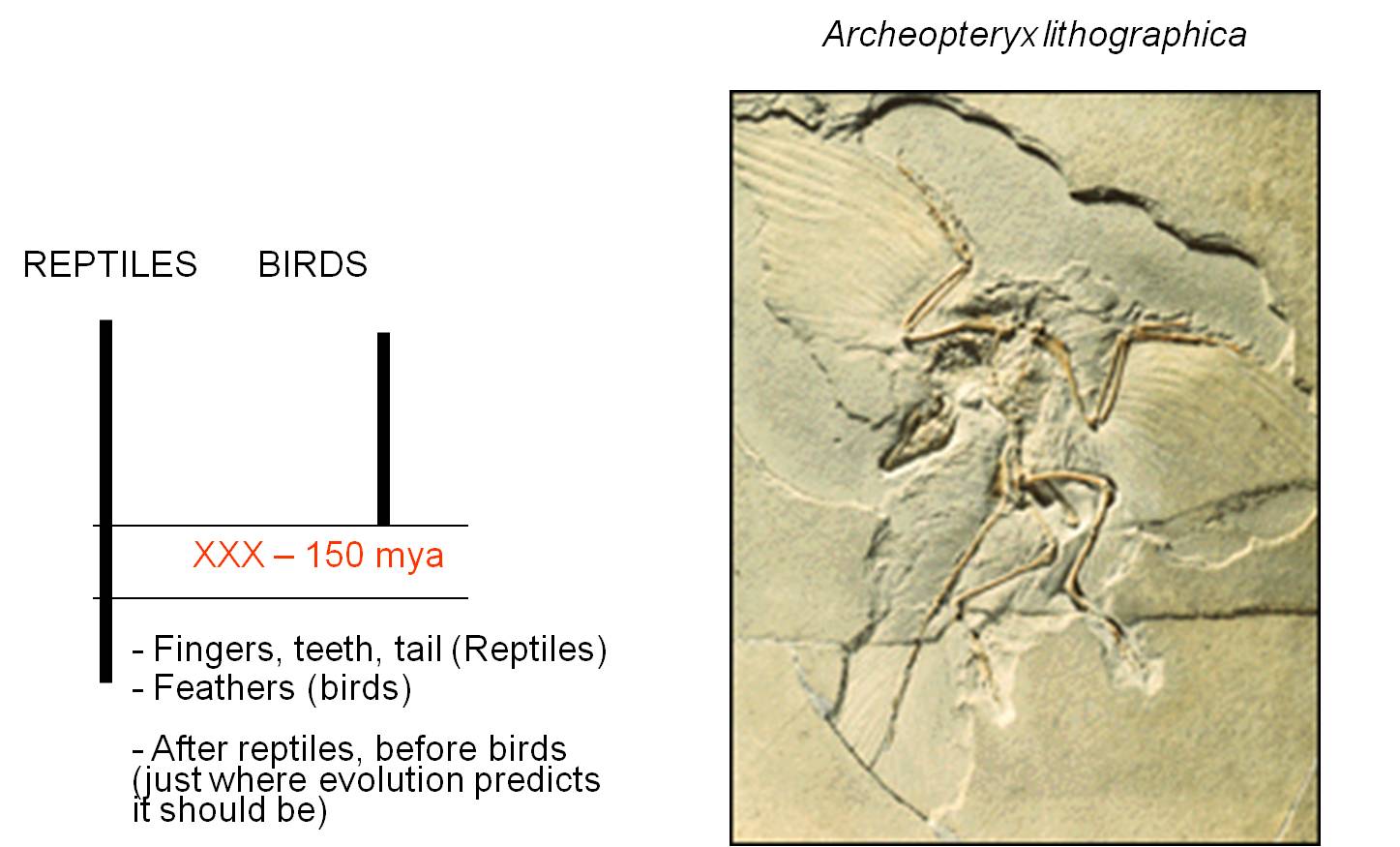

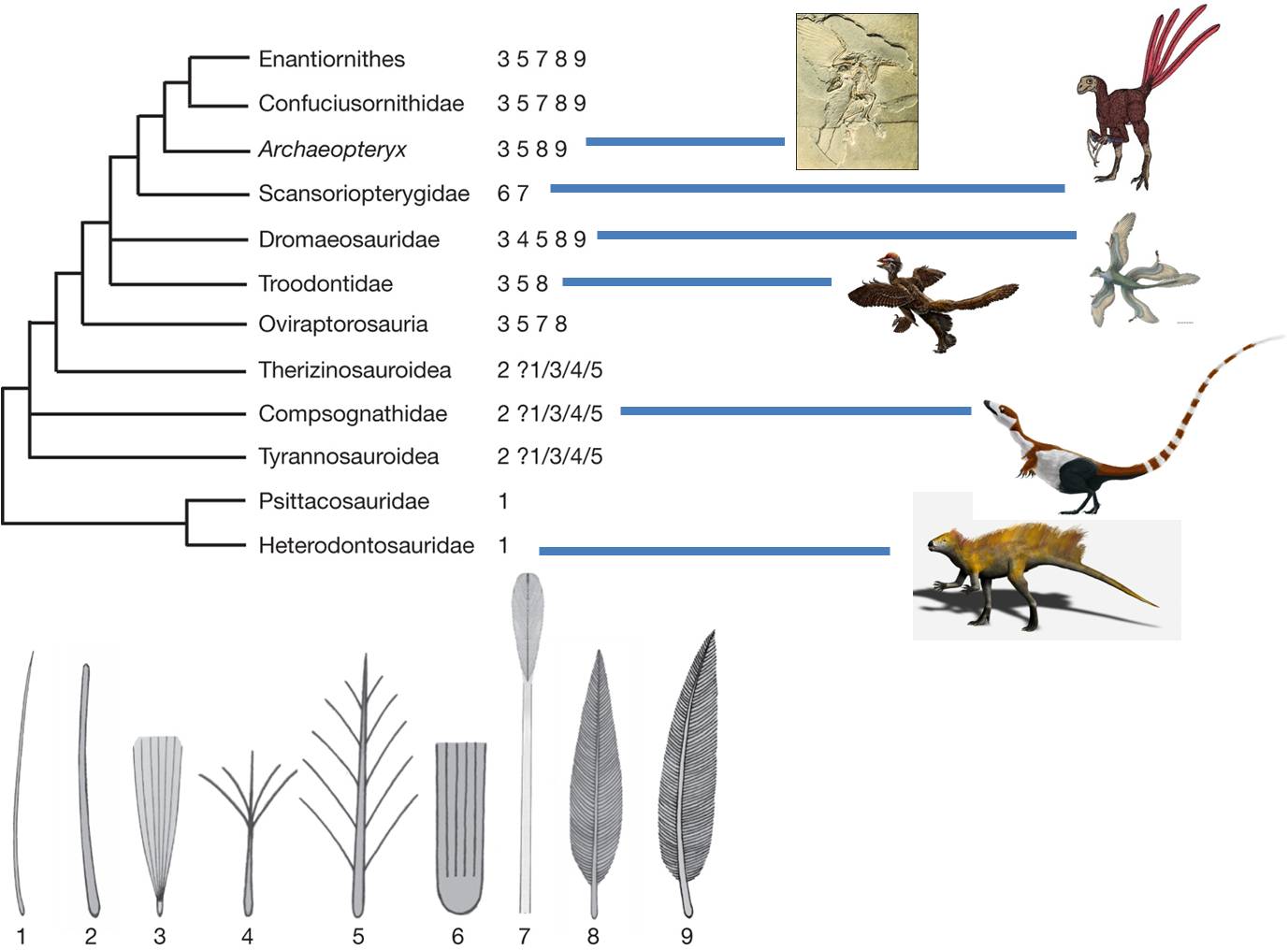

b. Archeopteryx lithographica and the evolution of birds

Archeopteryx has an intermediate morphology containing reptilian and avian characteristics. It has fingers, teeth, and a bony tail like reptiles (and unlike birds), but it has feathers like birds (and unlike modern reptiles). So, it had a combination of traits from two major groups. No birds today have teeth or fingers, and no reptiles have feathers. So, it is intermediate in morphology. But evolution PREDICTS something else about this organism. IF it was a biological link between reptiles and birds, then it would have to have lived after other reptiles (who were its ancestors) and BEFORE all true birds (who might be its descendants).

It is. The hypothesis has been tested by evidence from the physical world. Evolution is a testable, supported theory. Indeed, since 1861, further paleontological evidence suggests that birds didn't evolve from just any reptile, but from a specific group called the Maniraptoriformes. This group diverged from the Tyrannosauroidea, which includes Tyrannosaurus rex. Within the maniraptoriformes, we see a wide variety of feathered reptiles discoverd in China since 1990. However, the feathers are not only on the limbs and they are definitely not used for flight. In fact, in the oldest fossils of feathered dinosaurs, the protofeathers are only on the head and spine. A likely scenario is that feathers were first used for attracting mates. Selection for increased feather distribution provided the additional benefit of insulation and homeothermy. Finally, large feathers on the limbs might provide lift while climbing, running, or gliding, and selection could favor the acquisition of flight. This provides a nice example of how a complex trait - flight feathers - might NOT have evolved for that purpose intially.

|

|

| Archaeopteryx was the first intermediate discovered between reptiles and birds. | Now, paleonotologists have found numberous lineages of 'feathered dinosaurs', showing that the lineage leading to Archaeopteryx and modern birds was only one branch of ancestral, feathered animals. |

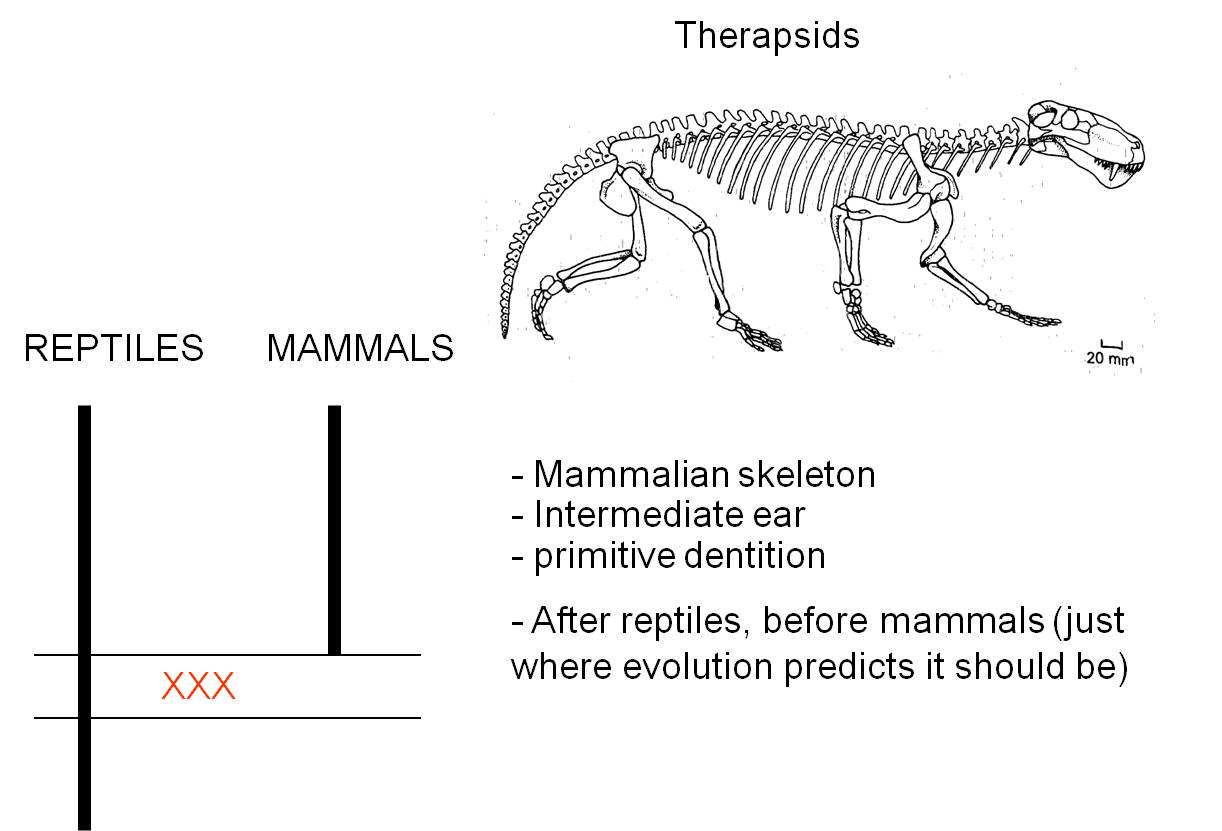

c. Therapsids and the evolution of mammals

The transition from reptiles to mammals is one of the most well-document transitions in the fossil record. Indeed, there is such a nice sequence that it is difficult to specify where the most important or instructive transition occurs. For our purposes, we will look at a group of organisms called the therapsids. Like reptiles, therapsids have several bones in their lower jaw, and one inner ear bone. Like mammals, they had specialized detition with incisor-like teeth at the front,and larger canines. Also like mammals, they walked with their legs underneath them, rather than out to the side like ancestral reptiles. Through the therapsid lineages, we have a very clear sequence of transitions that show how several of the lower jaw bones of reptiles became reduced and were eventually used as inner ear bones in the mammals. And of course, the therapsids fill the temporal gap between one group of ancestral reptiles and the more modern mammals - just as evolutionary theory and common ancestry predict.

|

|

| Therapsids were a group of reptiles that dominated during the Permian Period, 250 million years ago. | The evolution of the mammalian middle ear bones is beautifully preserved in the fossil record. The three middle ear bones in mammals (blue, yellow, pink) are homologous and descended from lower jaw bones of reptiles that became reduced in size and took on another function as their role in reptilian jaw function was assumed by the dentary bone (white). |

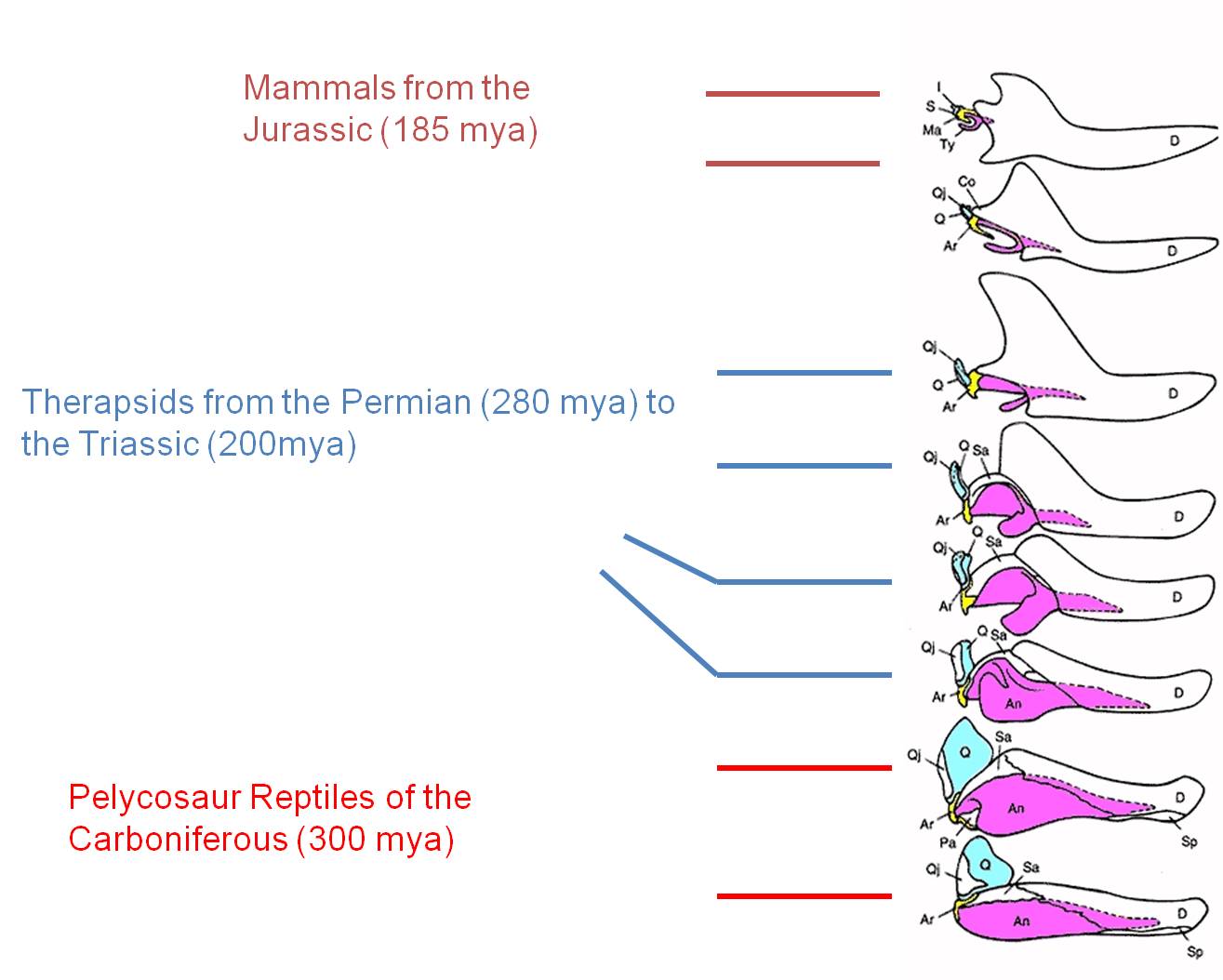

d. Australopithecines and the evolution of humans

Even Linnaeus recognized the morphological similarity between humans and apes (chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans). When we look at these species, the things that set humans apart are our upright stance and bipedal locomotion, our large heads, and our relatively short forelimbs. Ever since the first neanderthal fossil was found in 1856 and after Darwin wrote The Descent of Man in 1871, we have been reconstructing the phylogeny of our own species. There are many fossil species that form an excellent transitional sequence between ancestral primates and modern humans, again making it difficult to pick just one group. However, The Australopithecines provide a good and historically important group. In 1924, Raymond Dart discovered a very small skull of a juvenile primate that he named Australopithecus africanus, meaning "southern man-ape from Africa". Like other australopithecine fossils to follow, it had a short but ape-like snout with reduced canines. Dart suggested that the presence of this fossil in Africa, and the presence of chimps and gorillas in Africa, confirmed Darwin's hypothesis of an African origin of humans. This was highly debated by other anthropologists who believed that humans evolved in Europe or Asia. The discoveries of the Leakey's in Olduvai Gorge in the 1950's and 1960's, and the discovery of Australopithecus afarensis in the 1970's by Donald Johanson, supported the African origins model. The most complete single fossil of A. afarensis, known as the 'Lucy" fossil, shows the combination of traits expected in an intermediate, transitional species. The hip and the articulation of the femur and tibia show that the organism walked erect - a characteristic that is distinctly human. However, the cranial volume is very small - only 25% the volume of modern humans and equal to the volume of chimpanzees. However, other facial features are intermediate; the snout is shorter than in chimps and gorillas, but the canines are much larger than in humans. And again, these fossils fall before more human species and after more primitive primates; just as common ancestry and evolution would predict.

Yes, this is redundant; but it is redundant for a reason. There aren't just one or two fossils that 'conform' to the expectations of evolutionary theory. There are 100's of intermediates that provide tests and confirmation of evolutionary theory. One of the most frequent claims of creationists is that "there are no intermediate fossils". Well, you've seen quite a few, linking the major types of vertebrates. Darwin's theory of common ancestry predicted their existence, and scientists have tested this prediction by looking for physical evidence that could test this hypothesis. Although only Archeopteryx and neanderthals were discovered in his lifetime, we now have intermediates linking all major groups of vertebrates, confirming these hypotheses. It makes you wonder why these claims continue to be made, in the face of such overwhelming physical evidence.

|

|

| When discovered in 1974, Australopithecus afarensis was the oldest fossil of a bipedal hominid. | Since then, several more primitive bipedal species have been discovered. The fossil history of the hominid lineage has been very well described. |

1.

Gross Chromosomal Similarities

1.

Gross Chromosomal Similarities

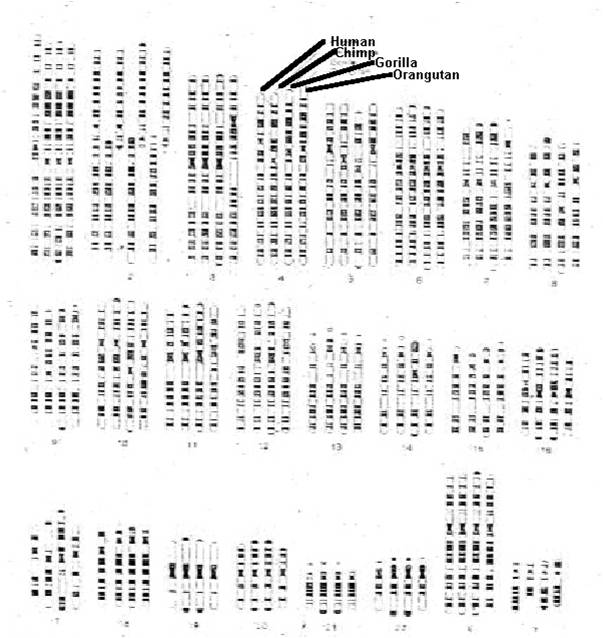

The most definitive tests of biological relatedness come by examining DNA. Why? Because the only place an organism gets its DNA is from its parents, their parents, their great-grand parents, and their ancestors. Barring the rare events of lateral gene transfer that can occur in some organisms, the only reason two organisms would have similar DNA is that they are biologically related. So, If I am accused of fathering a child, and my DNA is similar to that child's DNA, then I can be "convicted" of being related to that child. That is the only reason two organisms will share DNA - because they are biologically related. This pattern is reinforced by our understanding of meiosis and sexual reproduction, which explain why these patterns of relatedness occur. Now, when we see similarities among species in DNA structure, logical consistency demands that we propose the same hypothesis for the same pattern. In the figure at right, you see the chromosomes from a human, a chimp, a gorilla, and an orangutan. The most striking thing is the similarity in banding patterns across these chromosomes. Remember what those bands signify? The dark areas are heterochromatin, that have a low concentration of coding sequences. The lighter areas are euchromatin, where most of the genes are. So, we are looking at similarities in the large scale architecture of the genomes from these organisms. Evolutionary theory predicted that humans would have similar DNA to apes, and they do - even at the level of gross chromosomal structure. However, there is a major difference here; humans have n=23 while the other species have n=24. How can evolutionary biology explain this difference in chromosome number? Well, even the exception here proves the rule. The long #2 chromosome in humans - the first chromosome in thes econd set of chromosomes in the upper left corner of the figure - is banded like two of the chromosomes in other primates (shown next to it). A simple hypothesis would be that, at some point in the human lineage after divergence with chimp-like ancestors, these two chromosomes fused and became inherited as one unit. Can you remember an instance where chromosomes get stuck together and inherited as a single unit? It happens in translocation events, like in translocation Downs. And of course, this is not always deleterious to the organism - carriers for the translocation chromosome are phenotypically normal. A mating between two carriers could produce an offspring with the correct DNA content, but with two fewer chromosomes. Apparently, just such a modification may have occurred in the human lineage after divergence for the common ancestor we share with chimpanzees.

2. Mutational clocks

Mutations occur over time; the longer populations diverge from one another, the more mutational differences should accumulate between them. Many mutations have little effect on the phenotype - indeed, mutations in the non-coding intron regions of a gene, or in non-coding sequences between genes, have no effect on the phenotype. These mutations will be selectively neutral - and they should accumulate at a steady rate over time. If we can measure the mutation rate, then we can use this rate like a 'clock': we can count the number of mutational differences there are between the DNA from differnt populations, and then compute how long they must have diverged from one another to account for the genetic difference that we see.

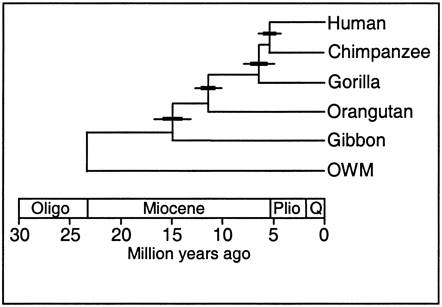

3. Genetic Phylogenies

Because

DNA comes from ancestors, similarity in DNA implies common ancestry. The greater

the similarity, the less time since their common ancestor; in other words, the

more "recent" their common ancestry. For example, human DNA and chimp

DNA is 98.4% similar in nucleotide

sequence, so they share a more recent common ancestor than either species shares

with gorillas - which are similar to both humans and chimps at a rate of 95%.

Now, some might claim that these similarities are analogous, representing

similarities between organisms that function in a similar way (but are not biologically

related). But, only 10% of the genome is a recipe for protein. Even

the 90% that does not code for protein, that is random sequence, still shows

this similarity. Even non-functional DNA is similar, so functional similarity

(ie., ANALOGY) can't be the answer... the similarity must be HOMOLOGOUS - the

result of common ancestry. Genetic phylogenies have been a powerful tool for

reconstructing the evolutionary relationships among broad categories of organisms

that are very different or similar morphologically. So, for instance, biologists

had long believed that all prokaryotes were closely related to one another,

and not closely related to the eukaryotes. Genetic analyses revealed, however,

that the Archaeans were more closely related to eukaryotes than to the other

prokaryotic group, the eubacteria. Likewise, genetic analyses show that fungi

are more similar to animals than they are to plants, and green algae is more

similar to plants than they are to other forms of algae. These relationships

can be understood in an evolutionary context. The eukaryotes evolved from a

type of prokaryote - and so should be more similar genetically, to this parental

stock of prokaryotes (the archaeans) than other prokaryotes (eubacteria). Green

algae gave rise to terrestrial plants, and so should be more similar, genetically,

to this closely related group (plants) than to other algal groups. This new,

more realistic view of the history of life is reflected in a new way to classify

organisms - based on common ancestry rather than common morphology, alone. For

example, as described above, some reptile groups are more similar to birds than

to other reptiles, and some reptile groups (though extinct) are more similar

to mammals than other reptiles. The new classification scheme takes a more systematic

approach, and groups organisms based on their phylogenetic relationships (grouping

crocodilians with their close relatives the birds, for instance), rather than

grouping organisms based on shared primitive characteristics (grouping crocodiles

with turtles, snakes, and lizards in "the reptilia" because they have

scales and lay shelled eggs). We will take a look at this later in the course.

Because

DNA comes from ancestors, similarity in DNA implies common ancestry. The greater

the similarity, the less time since their common ancestor; in other words, the

more "recent" their common ancestry. For example, human DNA and chimp

DNA is 98.4% similar in nucleotide

sequence, so they share a more recent common ancestor than either species shares

with gorillas - which are similar to both humans and chimps at a rate of 95%.

Now, some might claim that these similarities are analogous, representing

similarities between organisms that function in a similar way (but are not biologically

related). But, only 10% of the genome is a recipe for protein. Even

the 90% that does not code for protein, that is random sequence, still shows

this similarity. Even non-functional DNA is similar, so functional similarity

(ie., ANALOGY) can't be the answer... the similarity must be HOMOLOGOUS - the

result of common ancestry. Genetic phylogenies have been a powerful tool for

reconstructing the evolutionary relationships among broad categories of organisms

that are very different or similar morphologically. So, for instance, biologists

had long believed that all prokaryotes were closely related to one another,

and not closely related to the eukaryotes. Genetic analyses revealed, however,

that the Archaeans were more closely related to eukaryotes than to the other

prokaryotic group, the eubacteria. Likewise, genetic analyses show that fungi

are more similar to animals than they are to plants, and green algae is more

similar to plants than they are to other forms of algae. These relationships

can be understood in an evolutionary context. The eukaryotes evolved from a

type of prokaryote - and so should be more similar genetically, to this parental

stock of prokaryotes (the archaeans) than other prokaryotes (eubacteria). Green

algae gave rise to terrestrial plants, and so should be more similar, genetically,

to this closely related group (plants) than to other algal groups. This new,

more realistic view of the history of life is reflected in a new way to classify

organisms - based on common ancestry rather than common morphology, alone. For

example, as described above, some reptile groups are more similar to birds than

to other reptiles, and some reptile groups (though extinct) are more similar

to mammals than other reptiles. The new classification scheme takes a more systematic

approach, and groups organisms based on their phylogenetic relationships (grouping

crocodilians with their close relatives the birds, for instance), rather than

grouping organisms based on shared primitive characteristics (grouping crocodiles

with turtles, snakes, and lizards in "the reptilia" because they have

scales and lay shelled eggs). We will take a look at this later in the course.

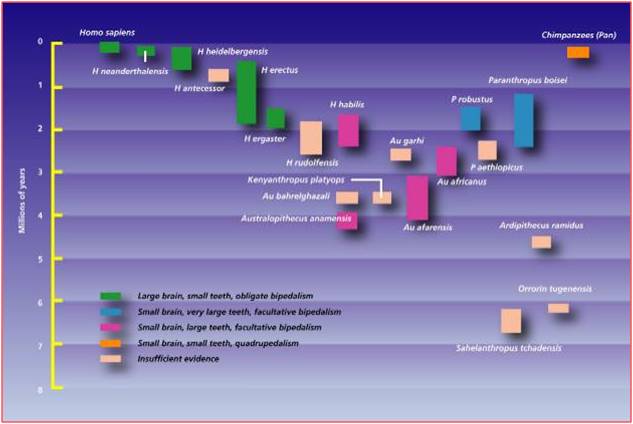

Both the fossil record and the pattern of genetic similarity among living species are presented as evidence of evolution and descent from common ancestors. If BOTH patterns due to the same phenomenon (common descent), then their patterns should be the same. In short, there should only be one tree of life, and both patterns should reveal that same tree. Indeed, we should be able to test the theory of evolution yet again, in a most remarkable way: we should be able to use the degree of genetic divergence to predict where (really "when"), in the sedimentary strata of the earth's crust, the common ancestor of two groups should be. Then, we should be able to go to that strata and find that common ancestral species.

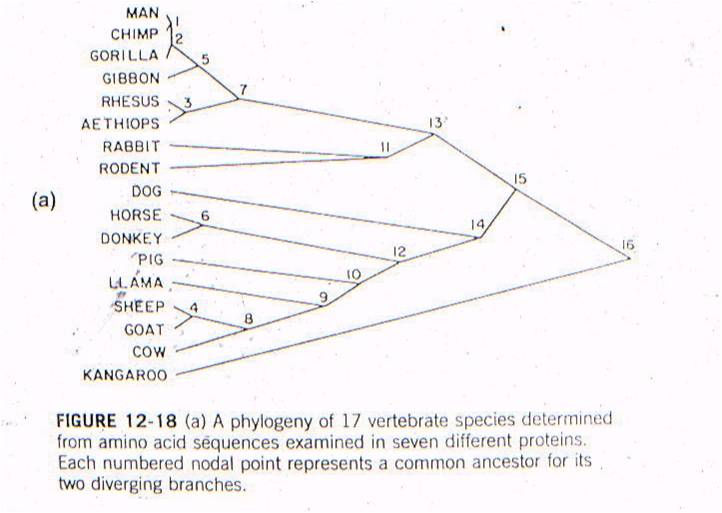

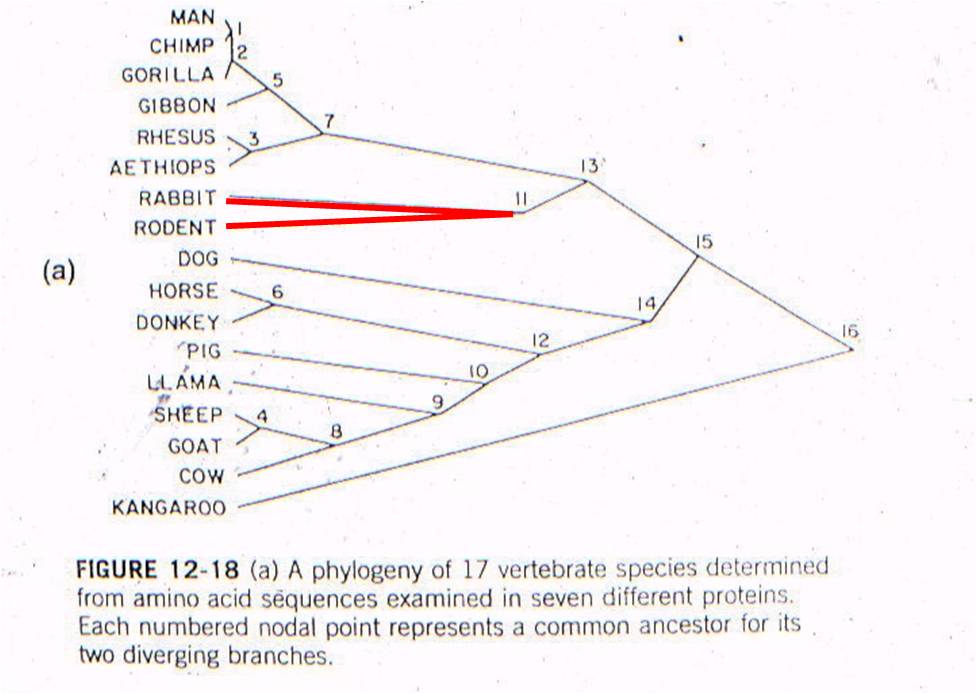

Let's

see an example of this type of test. All vertebrates have many of the same proteins,

but these proteins can differ in specific amino acid sequence. In this case,

the amino acid sequences for the same 7 proteins were sampled from 17 mammals.

For each possible pair of species, the minimum number of nucleotide substitutions

in the DNA, needed to explain the differences in the amino acid sequences, were

determined. For example, suppose humans have an argenine as the third amino

acid in collagen, while cows have lucine. Argenine is encoded by the codons

CGU, CGG, CGC, and CGA. Leucine is eoncoded by the codons CUU, CUG, CUC, and

CUA. So, although a two-base change could be responsibile (from CGU to CUA),

the minimum number of substitutions would be 1 - with just a change in the second

position (CGU to CUU). So, the minimum number of substitution mutations necessary

to explain all the sequence differerences between every pair of species is computed,

and then species are linked together based on sequence similarity. The number

at each "node" refers to the order of the clustering. So, the most similar pair

of species, of all the possible pair-wise combinations among these 17 mammals

(255 pairwise combinations) is humans and chimps - they are linked at 'node

1'. Then, gorillas are more similar to humans and chimps than any other

pair of taxa, so gorillas link to humans and chimps at node 2. Then, the

next most similar pair of taxa are Rhesus monkeys and Aethiops monkeys, linked

at node 3, and so forth. All placental mammals link together with one

another before any link to the sole marsupial, the kangaroo.

Let's

see an example of this type of test. All vertebrates have many of the same proteins,

but these proteins can differ in specific amino acid sequence. In this case,

the amino acid sequences for the same 7 proteins were sampled from 17 mammals.

For each possible pair of species, the minimum number of nucleotide substitutions

in the DNA, needed to explain the differences in the amino acid sequences, were

determined. For example, suppose humans have an argenine as the third amino

acid in collagen, while cows have lucine. Argenine is encoded by the codons

CGU, CGG, CGC, and CGA. Leucine is eoncoded by the codons CUU, CUG, CUC, and

CUA. So, although a two-base change could be responsibile (from CGU to CUA),

the minimum number of substitutions would be 1 - with just a change in the second

position (CGU to CUU). So, the minimum number of substitution mutations necessary

to explain all the sequence differerences between every pair of species is computed,

and then species are linked together based on sequence similarity. The number

at each "node" refers to the order of the clustering. So, the most similar pair

of species, of all the possible pair-wise combinations among these 17 mammals

(255 pairwise combinations) is humans and chimps - they are linked at 'node

1'. Then, gorillas are more similar to humans and chimps than any other

pair of taxa, so gorillas link to humans and chimps at node 2. Then, the

next most similar pair of taxa are Rhesus monkeys and Aethiops monkeys, linked

at node 3, and so forth. All placental mammals link together with one

another before any link to the sole marsupial, the kangaroo.

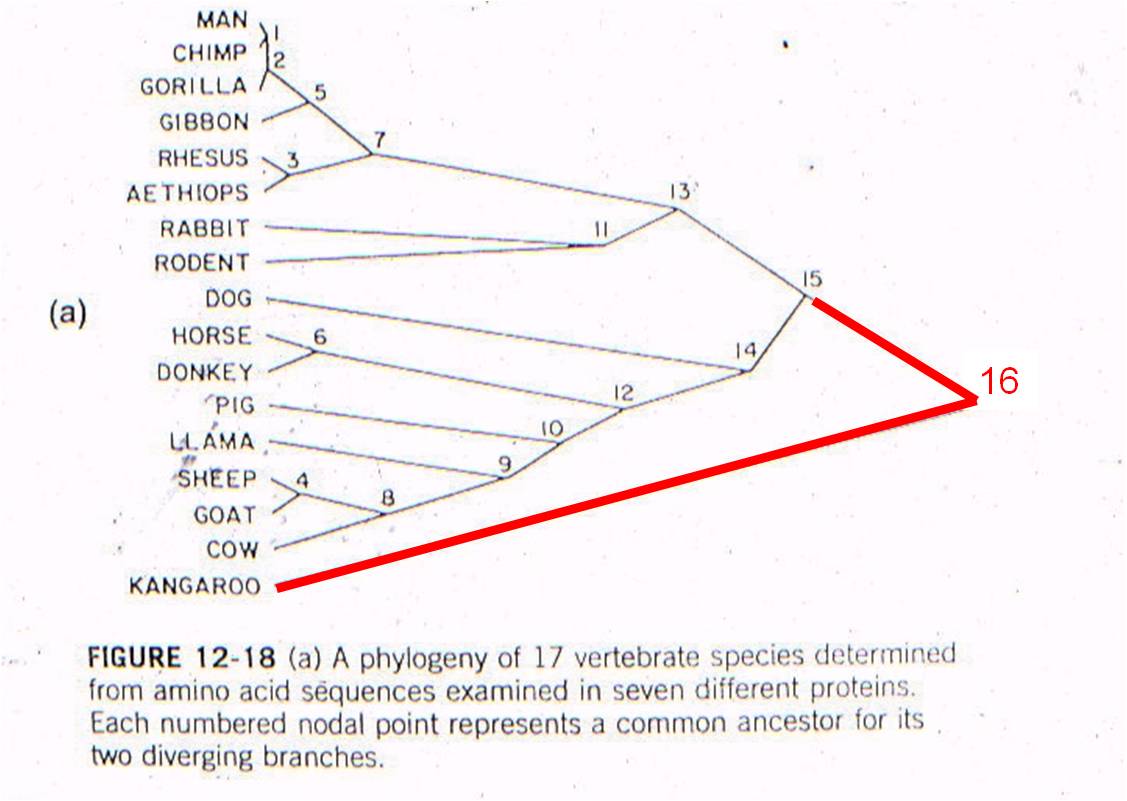

Now, this is just a clustering

procedure. It could be done on cars, nuts and bolts, anything. But

since it is done on life forms, we can test an evolutionary prediction.

Evolution suggests that organisms are similar because of common descent from

shared ancestors - represetned by these nodes. Species that are more similar,

genetically, should have a more recent ancestor than organisms that are more

different, genetically. So, there should be a relationship between 'time

since divergence' and 'genetic difference', as we explained above (mutational

clocks). Well, using the group of organisms that we have, we can describe what

evolution predicts that relationship should be:

IF: the oldest mammal in the fossil

record is ancestral to all more recent mammals, and

IF: the most different groups of mammals today (placentals and marsupials) are

descended from that ancestor, and

IF: the accumulation of genetic differences (mutations) occur at a constant

rate,

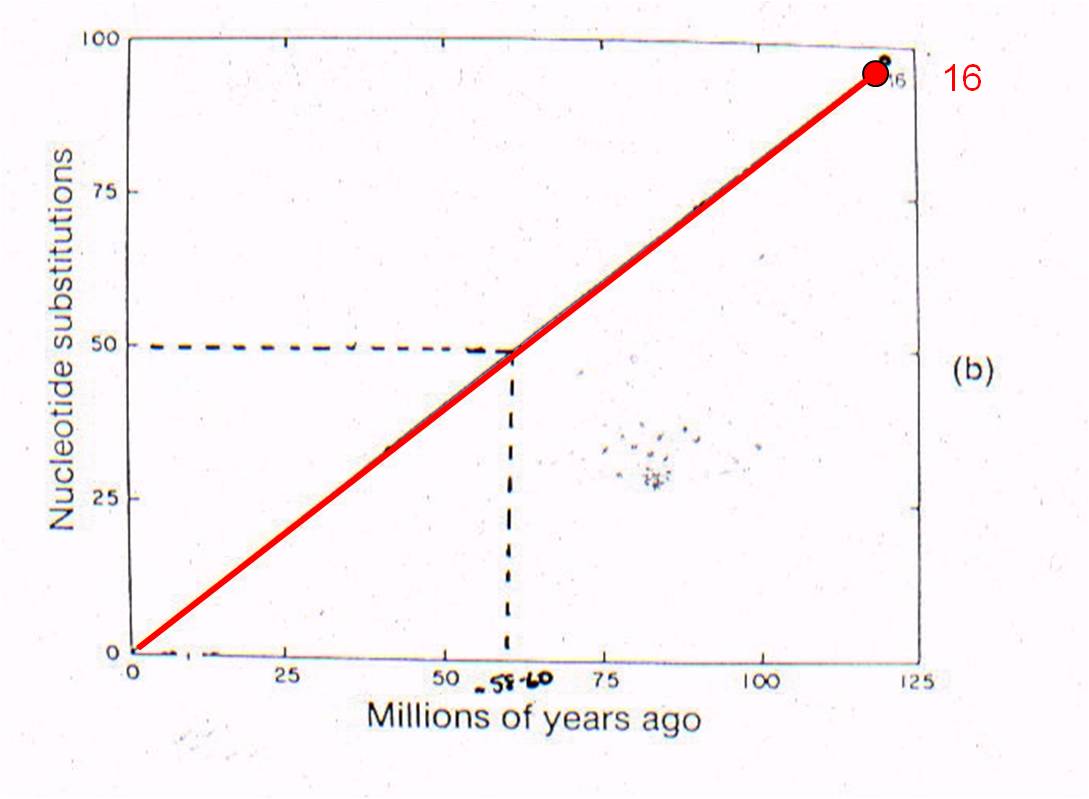

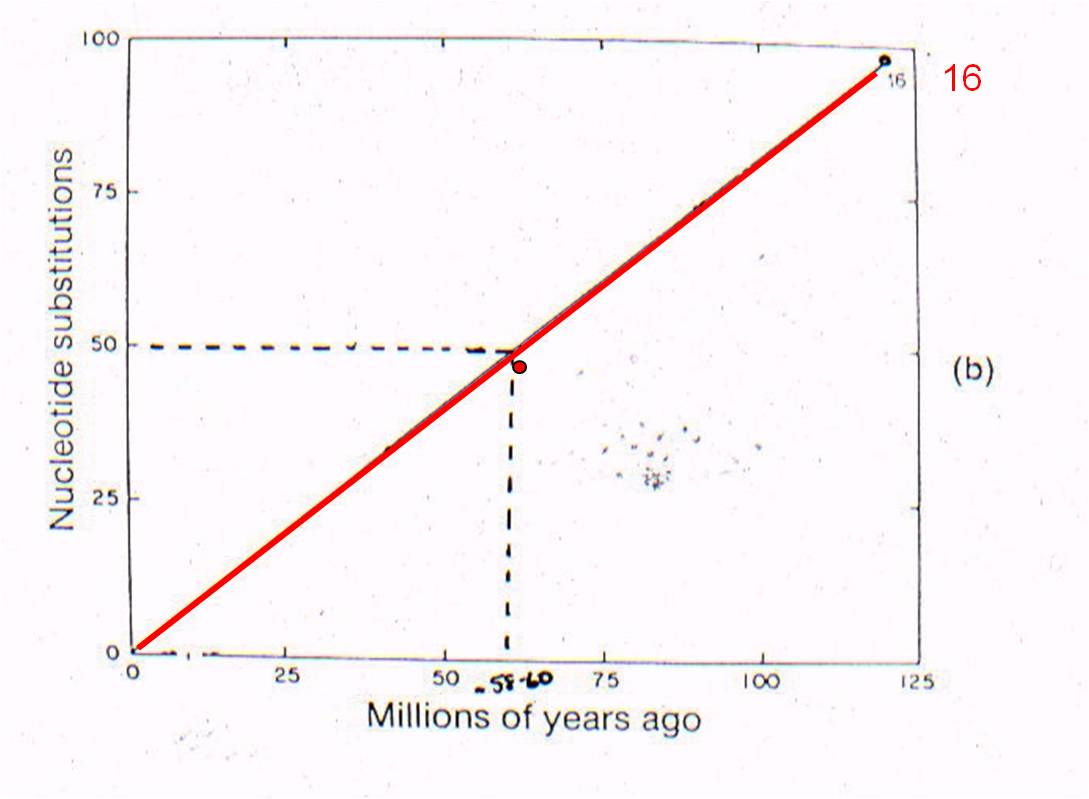

THEN: We can plot 'node 16' based on the age of the oldest mammal fossil (120 mya) and the genetic difference measured between marsupials and placentals (98 substitutions in DNA).

AND: if mutation rate is assumed to be constant, we can draw a straight line from 'node 16' to the origin. This is the predicted relationship between genetic similarity and time - predicted by the theory of evolution by common descent and the assumption of a constant mutation rate. So, evolutionary theory predicts that, if two mammals differ by 50 substitutions in these seven proteins, then it must have taken 58-60 million years for these differences to accumulate. In other words, their common ancestor should have lived 58-60 million years ago.

|

|

Well, rabbits and rodents differ by 50 substitutions in the DNA. Our model predicts that the common ancestor should live 58-60 million years ago. Well, where ARE the presumed ancestors in the fossil record? They are in strata that date to 58-60 million years old - just where the genetic analysis of LIVING species predicts they should be (see node 12, below).

|

|

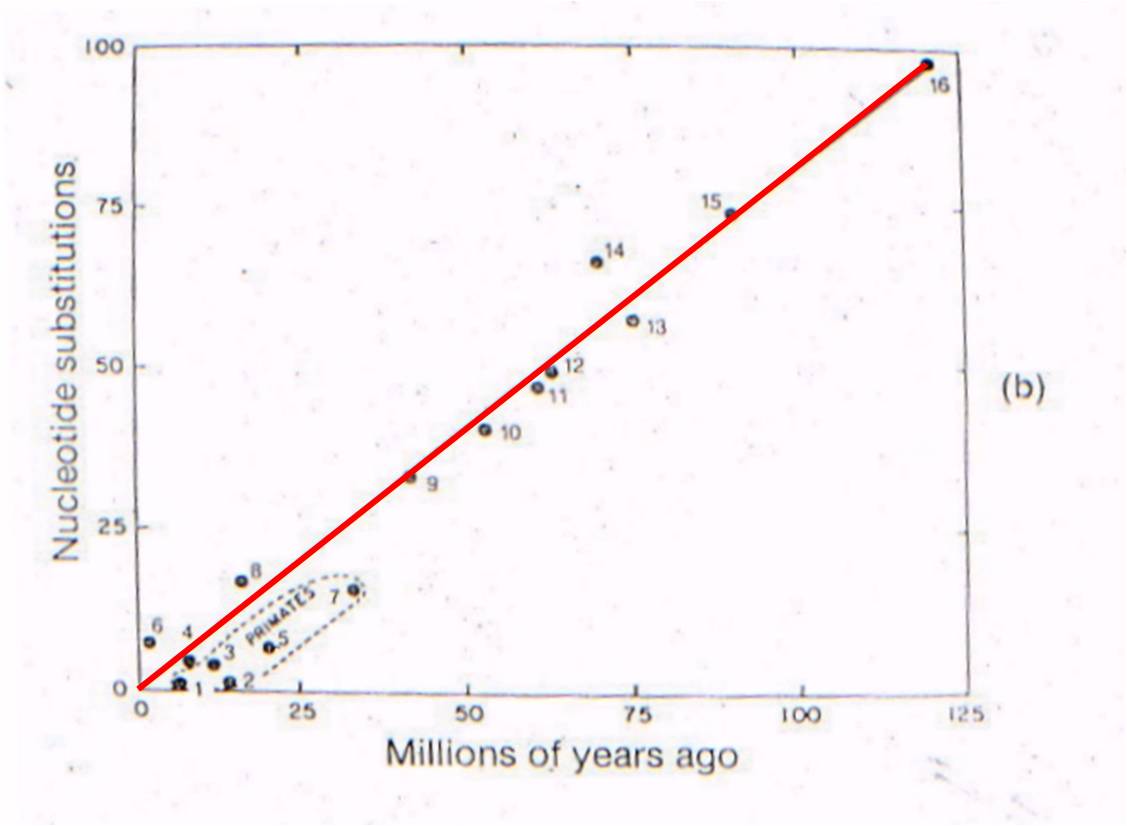

Now

lets consider where all the ancestral fossils are (figure to the right). The

intermediate fossils that link these taxa, and represent these numbered nodes,

are pretty much where our genetic analysis of existing species predicts they

should be - very close to the line. There is some variation - not all

points are exactly on the line - but our assumption of a constant mutation rate

is probably not explicitly correct for all genes, and probably introduces some

slight source of error. None the less, the data is strongly supportive

of our hypothesis - our evolutionary prediction has been confirmed by the data.

Now

lets consider where all the ancestral fossils are (figure to the right). The

intermediate fossils that link these taxa, and represent these numbered nodes,

are pretty much where our genetic analysis of existing species predicts they

should be - very close to the line. There is some variation - not all

points are exactly on the line - but our assumption of a constant mutation rate

is probably not explicitly correct for all genes, and probably introduces some

slight source of error. None the less, the data is strongly supportive

of our hypothesis - our evolutionary prediction has been confirmed by the data.

So, as we have seen before, evolution not only predicts the existence of common ancestors, but genetic analyses of living species can predict WHEN, millions to hundreds of millions of years ago, these different, extinct, ancestral species lived. (Remember those intermediate fossils? It's not just that they have a combination of traits, but they existed at the right time. Now we see genetics showing the same thing, in a PREDICTIVE way, like an good scientific theory should).

The only rational explanation that explains our ability to do this is evolution from common ancestors. This wouldn't work if evolution was false, radiaoctive dating was false, or genetic analyses did not reflect biological relatedness. All these hypotheses are confirmed by these experiments. Evolution is a predictive, explanatory model for how the universe works. It has been tested and supported in an extraordinary variety of ways.

Recognizing that natural selection and genetic drift were the two primary agents of evolutionary change, Ernst Mayr suggested that evolution would be particularly rapid when both of these agents were acting together - such as when small populations became isolated in a new environment. He thought that this would be happening quite frequently along the periphery of a species' geographical range, with small number of colonists becoming isolated from their ancestral populations in new habitats where they would be subject to new selective forces. He called this type of speciation "peripatric speciation".

In the 1970's, Stephen J. Gould and Niles Eldridge were paleontologists at the American Museum of Natural History. They were familiar with the inconsistency between Darwinian selection, which was often portrayed as a gradual, 'uniformitarian' process, and the pace of change in the fossil record. Although many lineages showed the type of gradual change that Darwin described, other lineages showed something quite different - long periods of morphological stasis interrupted by rapid periods of change. In short, they considered Darwin's last outstanding dilemma - why did the fossil record appear discontinuous, even where there were identified intermediates? In other words, even for lineages where intermediates were found, some species showed long periods of duration and others, seemingly associated with bursts of evolutionary radiations, appeared for a short time in local areas. Eldridge and Gould called this pattern 'punctuated equilibrium', suggesting that the typical lineage consisted of species that maintained long periods of morphological stasis (equilibrium) that were punctuated by rapid change. Changes were followed by descendant species that maintained their morphology unchanged for another long period.

C.

A Resolution

C.

A ResolutionIf Mayr was correct in concluding that most evolutionary change should occur in small, isolated populations, then the discontinuous, punctuated pattern described by Eldridge and Gould naturally follows. Consider the following scenario:

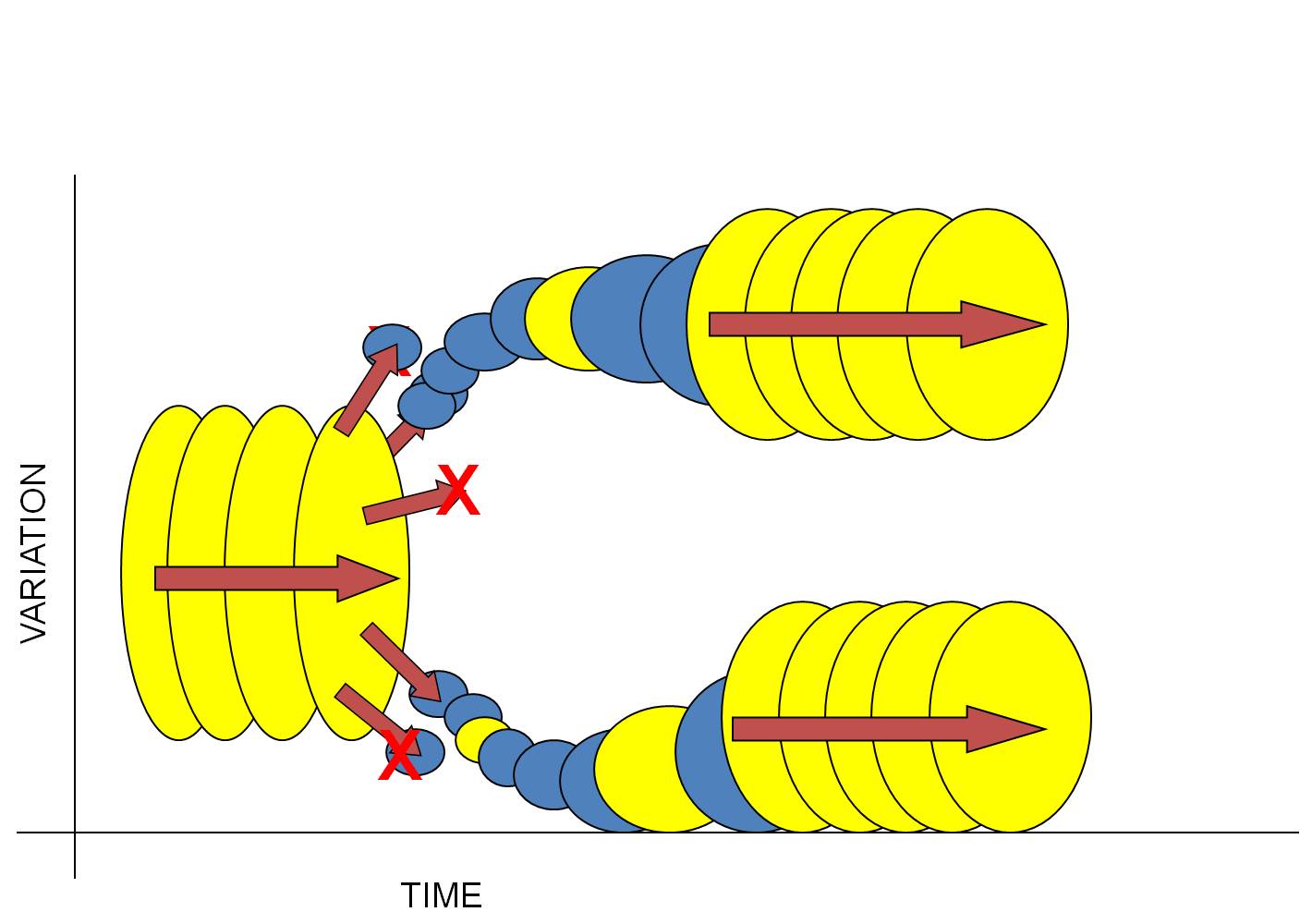

1) Consider a large, well-adapted population. Indeed, these two characteristics often go hand in hand. "Well-adapted" means that the species is able to efficiently harvest energy from the environment and convert it effectively into offspring. So, large populations that reproduce successfully should be well adapted to their environment. And as long as the environment remains stable, then the effects of selection should be weak... most organisms have an adaptive genotype and there is little differential reproductive success among them. Likewise, if the population is large, then the effects of drift are small. So, a large, well-adapted population should change little over time (equilibrium). This is represented by the large yellow circles to the lef - the ancestral species - changing little over time.

2) Now insert Mayr's concept of peripatric speciation. Large populations often have a large geographical range. And if small populations 'bud-off' this large range into new habitats, then both drift (small populations of colonists) and natural selection (new habitat) will probably either change the genetic structure of the population rapidly, or cause the extinction of the population (because the narrow range of genetic variation contained in the small population of colonists is unable to tolerate the environmental conditions in the new habitat). This is represented by the small blue circles budding off last large yellow one.

3) So, most subpopulations colonizing new habitats will go extinct (this may be why the population didn't live there, in the first place). But occasionally, a small, genetically different subset may be able to tolerate the conditions in a new environment and persist. It will adapt rapidly to these new conditions, changing (evolving) rapidly as a consequence of drift and selection. These ideas are represented by some blue populations going extinct (red X), and others changing rapidly - a steep slope in variation over time.

4) Over these generations, when the population is small and changing in response to the environment, it is unlikely that each 'step' or 'transitional species' in this sequence will preserve a fossil. The populations are small (so it is unlikely that the rare event of fossilization will preserve a member of the species), and each morphologically distinct population is also short-lived; this will also reduce the chances that a member of the population gets fossilized (before it has evolved again). So, these small, rapidly changing populations are unlikely to each leave a fossil - and unfortunately, this may be just where the most evolutionary change is occuring in the lineage. (Yellow circles, both large and small, are the populations that leave a fossil.)

5) Now, as a population adapts to its new habitat, it should (almost by definition) become more effective at converting energy from the environment into successfully reproducing offspring. After all, this is what natural selection does - it increases the reproductive success of the population. So, as a population adapts to the environment, it should increase in size, too.

6) So, the population is becoming larger and better adapted to the environment. So, the effects of selection and drift should decline, and the rate of change should slow. Eventually, we have another species that is large and well-adapted to its environment, changing little over time. (The sequence of large yellow circles at the right of the figure).

This model of evolution explains Darwin's last dilemma - the apparent discontinuity of the fossil record. A modern understanding of evolution, that appreciates the effects of selection and drift acting on structural and regulatory genes, will cause rapid change in small populations and little change in well-adapted populations. Because fossilization is a rare event, small, short-lived populations will be far less likely to leave a fossil than a large, long-lived population. For this reason, because speciation is concentrated in local populations changing quickly, the fossil record will appear discontinuous. Rather than "explaining away" this discontinuity, Eldridge and Gould explained it as a necessary consequence of a modern understanding of the pattern and process of evolution.

Study Questions:

1. What is epigenesis?

2. How are gene duplication and segmentation similar in terms of introducing evolutionary novelty?

3. What are homeotic genes, and what type of protein do they code for?

4. Explain homologous structures in terms of the regulation of developmental genes.

5. What is a 'morphological species", and what are two problems that arise when we use this method for identifying species?

6. State the 'biological species concept'.

7. If a rock has a ratio of Ar:K of 7:1, how old is it?

8. What are the two key characteristics of transitional fossils?

9. Why is Ichthyostega considered to be an intermediate fossil?

10. What characteristics make Archaeopteryx an intermediate fossil?

11. What characteristics do therapsids have that make them intermediate fossils?

12. What characteristics do Australopithecines have that make them intermediate fossils?

14. Explain the logic of using genetic differences and mutational clocks to determine the time since a common ancestor.

15. Does the fossil record conform to these predictions? Describe an example.

16. Use the concepts of peripatric speciation and punctuated equilibrium to explain why we don't have complete sequences of fossils that preserve every morphological change that occurs in a lineage.